About This Exihbit:

Military History of the Czech Lands: From Bohemia to the Czech Republic

It all started with…

Part I: Czech and Czechoslovak Military History

I. Medieval and Early Modern Period

Founding the Kingdom of Bohemia

Sources:

Berend, Nora, et al. Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900 c.1300. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Britannica Editors. "Otakar II". Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 Aug. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Otakar-II. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Britannica Editors. "Wenceslas II". Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 Sep. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wenceslas-II. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Britannica Editors. "Wenceslas III". Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Oct. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wenceslas-III. Accessed 4 December 2025.

Horáková, Pavla. “Bohemian Royal Premyslid Dynasty Died out 700 Years Ago.” Radio Prague International, 4 Aug. 2006, english.radio.cz/bohemian-royal-premyslid-dynasty-died-out-700-years-ago-8617097.

Jiřincová, Barbora, and Alexandra Vukovich. Slavic Ancient Origins. Collector’s Editions ed., Flame Tree Collections, 2024. (230-286)

McEnchroe, Thomas. “Wenceslas II. – the King Whose Empire Stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Danube.” Radio Prague International, 8 Mar. 2019, english.radio.cz/wenceslas-ii-king-whose-empire-stretched-baltic-sea-danube-8136646.

Monroe, W. S. Bohemia and the Čechs: The History, People, Institutions, and the Geography of the Kingdom, Together with Accounts of Moravia and Silesia / by Will S. Monroe. G. Bell, 1918, 1918. (16-49)

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948, 18-39.

R. T. Williamson. “King John of Bohemia, and the Crest of the Prince of Wales.” Welsh Outlook, vol. 19, 1932, pp. 162-63.

Stefan, Ivo, et al. “The Archaeology of Early Medieval Violence: The Mass Grave at Budeč, Czech Republic.” Antiquity, vol. 90, no. 351, 2016, pp. 759–76, https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.29.

“A Brief History of the Czech Republic.” Czechuniversities.Com, Discover Czechia, 31 Aug. 2019, www.czechuniversities.com/article/a-brief-history-of-the-czech-republic.

“Bohemia.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 2 May 2025, www.britannica.com/place/Bohemia.

“Říp Mountain.” Zámek Mělník, 14 May 2018, lobkowicz-melnik.cz/en/rip-mountain/#:~:text=As%20the%20legend%20goes%2C%20Forefather.

Images:

“20190816 Relief with emperor Charles IV, West facade of St. Vitus Cathedral 1416 5336” by Jakub Hałun, CC BY-SA 4.0.

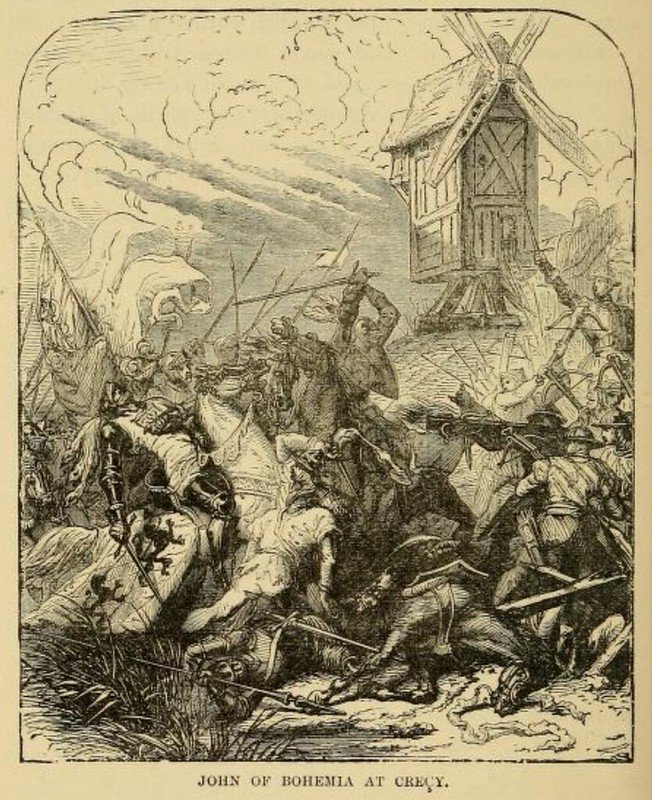

"Middle Ages - John of Bohemia at Crecy" by History Maps, Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“Ottokar II of Bohemia on the Marchfeld in 1260” by Emil Nietzsch Sohn (1891), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Portret van Wenceslaus II, RP-P-1874-12-123-2" by Rijksmuseum, CC0 1.0.“Premyslid Dynasty Family Tree” by Daniel0067, CC BY-SA 3.0.

“Royal Banner of the Kingdom of Bohemia” by Dragovit, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Before the Czech Republic and Czechoslovakia, there was an area that would become the Kingdom of Bohemia. This land was first settled by the Slavic peoples. According to legend, it was referred to as “the promised land, abundant in milk and honey” by Forefather Čech, a mythological Czech figure who climbed Říp Mountain and surveyed the surrounding landscape before he and his people settled there. The Bohemian tribes in the 8th century accepted the influence of the Moravians. Slavic peoples, beginning with Prince Mojmír I (r. 830–846), would create a political state that encompassed Bohemia, along with parts of Hungary, Poland, and other territories. Greater Moravia would last until the late 9th century. They were replaced with the Premyslid dynasty, with Borivoj 1 (r. 852-889), a relative of the Moravians, and his more well-known wife, Ludmilla. Their son Spytihnev I (875-915) brought reformations and prosperity to Bohemia while being baptized by a Slavic archbishop. Christianity itself began to take hold with Bohemian leaders adopting the religion in 845 as a political maneuver with the Holy Roman Empire, with the Premyslid dynasty formally adopting Christianity as their official religion into the early 900s. They joined the Holy Roman Empire as the Duchy of Bohemia in 950 amid the rise of the state under the Premyslid Dynastyře until 1306. They were established as a vassal kingdom in 1198 by Přemysl Ottokar I. Eventually, the kingdom was absorbed into the Austrian-based Habsburg Empire in 1526.

This was an age of knights, men-at-arms, and armored horses ruled by princes and emperors, where elaborate and intricate combat rituals were performed. Up until the 12th century, however, military conflicts in the Early Middle Ages were considerably brutal in retrospect when analyzing archaeological finds such as mass graves. One such grave was found in 1982 in the stronghold Budec near Zakolany in central Bohemia, with upwards of 33 to around 60 bodies identified by researchers. They were believed to be part of the site of a massive battle stemming from Boleslav I’s attempts at removing his brother from power in 935 A.D. A member of the Přemyslid dynasty who had priorly murdered his ruling brother Wenceslas, Boleslav I (r. 935-972 A.D.) renounced the Franks and sought to centralize power. The fort, built on top of a hill, had several hundred occupants, including a substantial military garrison. It saw the most combat during the late 9th and 10th centuries. Most of the bodies were young adult males who were found to have died from slash wounds using swords and similar weapons, with a surprising number of bodies (10-24) that were decapitated being identified. The majority of the dead are believed to be defenders of Budec. The damage inflicted showcased how large-scale extreme violence, including this massacre, was commonplace around this period.

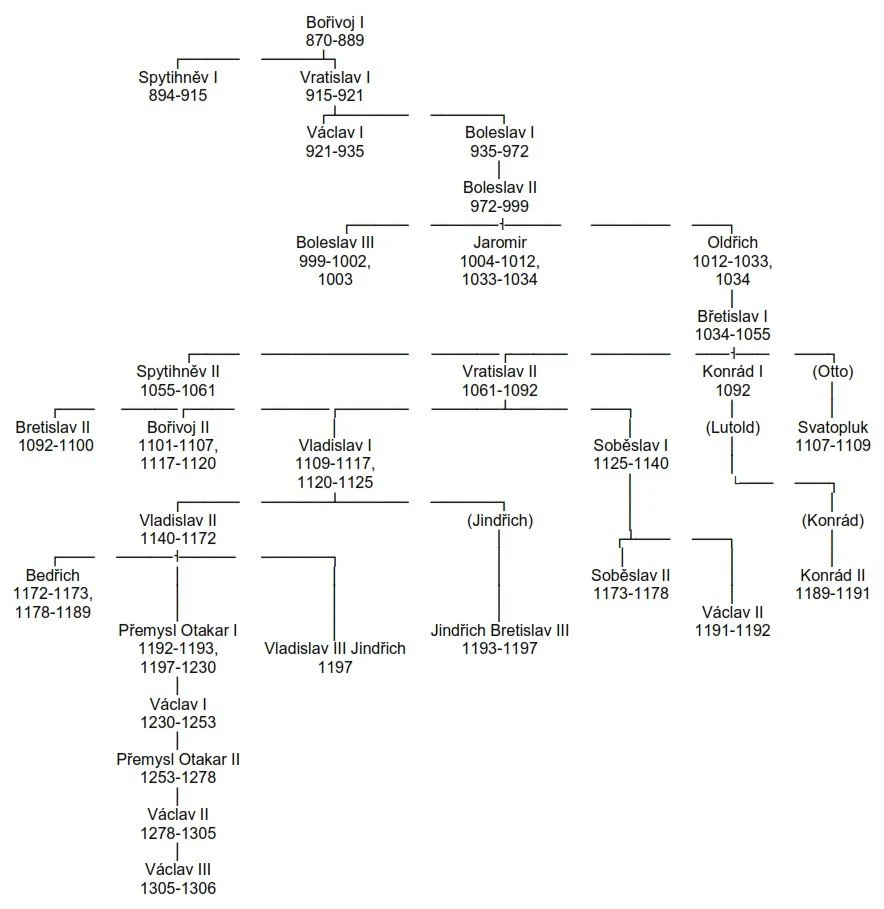

Family tree of the dukes and kings of the Přemyslid royal dynasty.

The Bohemian people came together from Slavic tribes united by a hereditary ruler who created an army of warriors for both military and administrative duties. When the Great Schism of 1054 occurred, the Kingdom of Bohemia allied with Western Europe as it sought to separate itself from the Byzantines and divisions that other Slavic tribes faced. Ruled over by the Přemyslid Princes, reunification in the nation was not an easy feat, with King Wenceslas facing struggles for power from his own family and the local rulers who fought amongst themselves. He was succeeded by his ambitious brother Boleslav I, who wished to make Prague the center of importance, adopted Christianity as the state religion, and sought independence from the Holy Roman Empire. He later lost to Emperor Otto I but retained autonomy and served together in later conflicts. People were increasingly reliant on the estates of warriors, with those protecting merchants along their routes becoming a significant economic class. Additionally, power struggles existed not just between rulers but also with their warriors, with one of Vladislav I’s sons being deposed from power in 1193.

King Přemysl I would take control of Bohemia and Moravia in 1197 and faced opposition from the Primate of Prague. German emperors had long sought to subjugate Bohemia under their rule. Wenceslas I, his son, was a fan of chivalry and the Gothic. German settlers began settling in towns and villages alongside the border, with this trend being viewed as colonization efforts. This was not the only factor, as Europe faced a massive Mongolian invasion across Eastern and Central Europe. Referred to as the Tatars, they eventually withdrew and even gave Bohemia the title of “Shield of Europe”. There were heavy losses, however, with Eastern Moravia and Slovakia devastated by the invaders. In response to the invasion, many castles were established not only as fortresses of protection but also as administrative and economic centers.

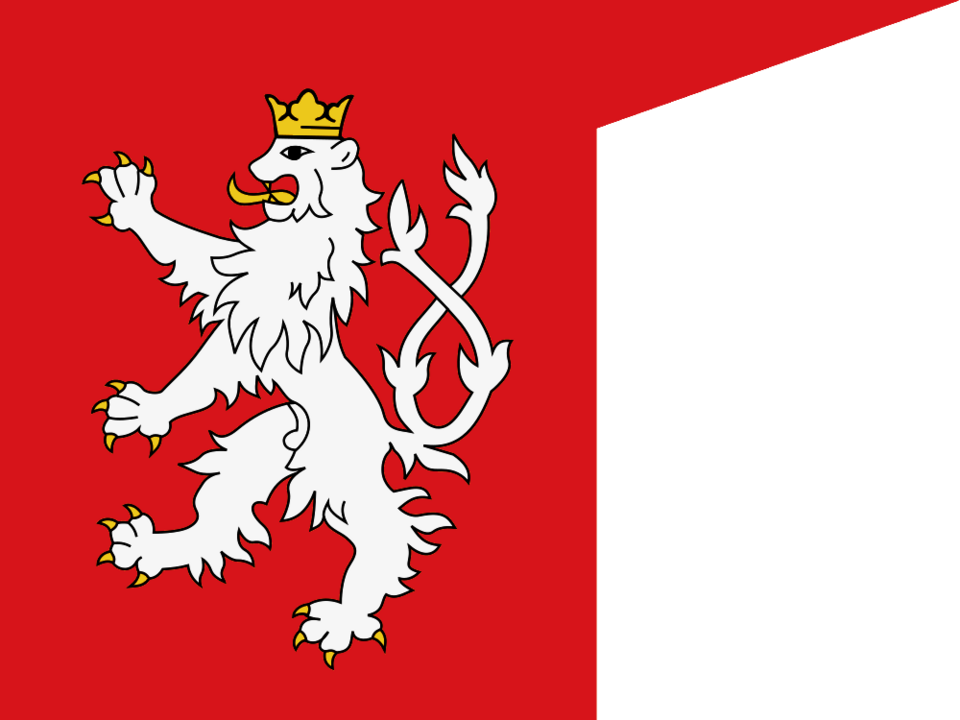

Heraldic banner of the Přemyslid dynasty, also banner of Saint Wenceslas and the Duchy of Bohemia.

Přemysl Otakar II, son of Wenceslas I, became famed for his military expansionism, leading campaigns such as his crusades against Prussia, his conflict with Hungarian King Bela leading to the conquest of the Alps, and more. He became the Duke of Austria in November 1251, and later the King of Bohemia and Moravia in September 1253. Reigning a domain that stretched from the Adriatic Sea east of Italy to Silesia, he was considered as one of the most powerful princes of the Holy Roman Empire. He became known as the “Iron and Golden king,” turning the lands of Bohemia and Moravia into a powerful empire that dominated Central Europe.

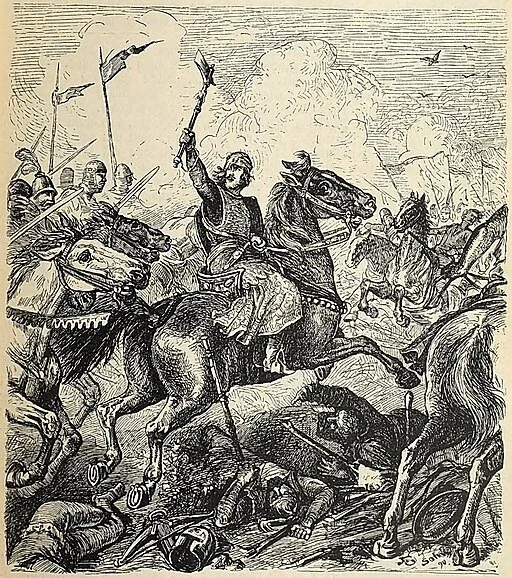

1891 painting depicting Ottokar II of Bohemia (1233-1278) at the Battle on the Marchfeld.

While his militarism emboldened the Kingdom to a new golden age, it had also led to both foreign leaders and the Czech nobility feeling alienated. King Otakar II’s ambitions soon shifted to desiring the throne for Germany, becoming envious of King Rudolf of the Habsburg dynasty. Soon, he was forced to relinquish all territories outside of Bohemia and Moravia to the German crown, as deemed by the Imperial Diet at Nuremberg. His reign would end with a disastrous defeat at the Battle on the Marchfeld on August 26, 1278. King Otakar II made a desperate attempt to regain control of Austria and other lost regions, marching towards Vienna. With both armies encountering each other in Dürnkrut, Austria, Otakar II’s army would see devastating losses, with the king losing his own life on the battlefield.

Consequently, his 7 year old son, Wenceslaus II, would be thrust into the Bohemian throne. Immediately held captive by his cousin Otto V of Brandenburg-Salzwedel, he would be isolated from his family, locked away at Bezděz castle and later the fort of Spandau. His captor would assume power from being the Margrave of Brandenburg to regent of Bohemia, sending his armies to ransack the kingdom with the help of Otto IV, Margrave of Brandenburg-Stendal. Wenceslaus II would be freed and reunited with his mother 5 years later, returning to Prague in 1283. However, he learned of his mother’s marriage to Zaviš of Falkenstein, a man who helped betray his father during the Battle on the Marchfeld, and who held ambition for controlling the kingdom. Though Wenceslaus II initially treated Zaviš cordially and surprisingly came to see him as a father figure, he understood Zaviš posed a potential threat to his claim to the crown. He would have Zaviš arrested by 1289, with his faction disbanded and his beheading the following year.

Portrait of Wenceslaus II (1271-1305) made by artist Gottfried von Kempen in Cologne, Germany.

With King Wenceslaus II’s rule now unimpeded, he would continue his father’s legacy of expanding Bohemia. He redistributed power amongst the nobility and clergy to prevent monopolization, as well as gaining record economic capital with the kingdom’s silver mines. He also flexed his diplomatic prowess with a focus of Eastern expansionism, compared to his father’s push to the south. Upon annexing annexing most of Upper Silesia, he would go on to succeed Przemysł II to rule over Poland. He even expanded the Přemysl dynasty’s domain to Hungary, although he declined the crown in favor of his son, Wenceslaus III.

He installed his son as the Hungarian King in 1301, but Wenceslaus III was seen as an immature and weak leader. With King Wenceslaus II dying from Tuberculosis in 1305 at 33, his son abandoned Bohemia’s claims to Hungary. His son would spend the year partying and drinking away his sorrows until he returned to reclaim the Polish crown in 1306. At just 15 years old, Wenceslaus III was shockingly assassinated in Olomouc, killing the Přemyslid dynasty off. Although the kingdom was eventually reduced to just the Duchy of Bohemia and the Margraviate of Moravia, and the House of Přemysl had collapsed by 1306, the region maintained its status as an influential powerhouse in Europe.

During this tumultuous period, Henry VI of the House of Goizi, Duke of Carinthia and Landgrave of Carniola, would ascend to the throne as King of Bohemia. His succession in 1306 would only last a short while, however, as it went against his former ally, King Albert I of Germany. He sought to enthrone his son, Rudolf I of the House of Habsburg to the throne, temporarily displacing Henry VI with an invasion of Prague Castle before Ruldoph’s sudden death. Despite regaining the throne in July 1307, he was dismissed as an ineffective ruler by the Bohemian nobility. His rule was contentious both internally and from the Habsburgs. King Henry would be succeeded by John “the Blind,” the first King of Bohemia to come from the House of Luxembourg. They would come to control the Bohemian crown lands via marriage with Eliška Přemyslovna, daughter of Wenceslas II. John (Jan) was the son of Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, who allowed this marriage to stabilize the region and secure Luxembourg's control of Bohemia.

Painting depicting Henry VI, Duke of Carinthia (1265-1335)

Ascending to the throne on August 31, 1310, King John of Bohemia first needed to secure his position, amidst several factions of nobility vying for control. With King Prague in disrepair after the Habsburg raid, King John made “inaugural diplomas” to Bohemian and Moravian aristocrats, balancing the scale of power while renewing trade between the two regions. His diplomacy renewed trade with Central Europe while jumpstarting the Czech economy. Tensions would be calmed with the Habsburgs over Moravian borders, and the House of Wettin, princes of Saxony, would be pushed to agree to terms over the northern states. He was even named as Imperial Vicar of the Empire by his father until his death in 1313, with a spot on the imperial throne now in contention. This would bring him into direct rivalry with Fredrick of Habsburg and Louis of Bavaria.

Wary of Frederick, John decided to support Louis for the throne at the diet of electors in 1322. This was partly to avoid strengthening the Habsburgs and partly because an alliance with France faced resistance within the Roman Empire. This support would come with Louis guaranteeing the holdings of Silesia, Meissen, Cheb, and the Upper Palatinate to the Kingdom of Bohemia, although not immediately. His reign faced difficulty as he relied heavily on foreign advisors, which alienated the local aristocracy. The nobles, who had gained significant power after the death of Wenceslas II, resisted any attempt to diminish their influence. Internal conflicts among aristocratic factions further destabilized the kingdom, and John’s frequent absences worsened communication and governance. He established heavy taxes and became known for his excessive spending. His struggles to communicate with the Bohemian and Moravian lords would even affect his marriage.

Old drawing depicting John of Bohemia (1296-1346), perishing on the battlefield at the Battle of Crécy.

Concerned about the rising ambitions of the Czech aristocracy and what they may do to John’s family, he sent them away to the castle of Mělník. His own son, Wenceslaus IV, would be raised and taught within the French court. This was due to John becoming more aligned with France over the years, allying with them and going on to fight with King Philip VI of France against the English under King Edward III. Even while having gone blind by the time he reached 50, King John continued to participate in battles. Joining the Hundred Years' War had unfortunately strained John’s relationship with Louis due to the latter’s alignment with England. This was worsened as King Philip VI suffered several tactical defeats at the hands of the English. This would culminate in John’s death at the Battle of Crécy on August 26, 1346, being slain in hand-to-hand combat.

Roman Emperor Charles IV (1316-1378), also known as Karolinum Karel IV. He ruled as King of Bohemia from 1346 until his death in 1378.

The first Bohemian emperor of the Holy Roman Empire would be named Emperor Charles IV, formerly known as Wenceslaus IV (May 14, 1316— Nov. 29, 1378) of the Luxembourg dynasty. Before he rose to the throne, his father John, King of Bohemia, had slowly been transferring more and more powers to him. This accelerated following Wenceslaus IV’s return from France in the 1330s, signaling John held grandiose plans for his son’s rule. Charles IV would succeed John in 1346 following his death as the King of Bohemia, and as the Holy Roman Emperor. He sought to transform Prague into the administrative capital of the empire through diplomacy and help from the Catholic Church. With limited military prowess, he was more hesitant with going to war compared to his predecessors. He would acquire new territory, which extended from Luxembourg to Hungary.

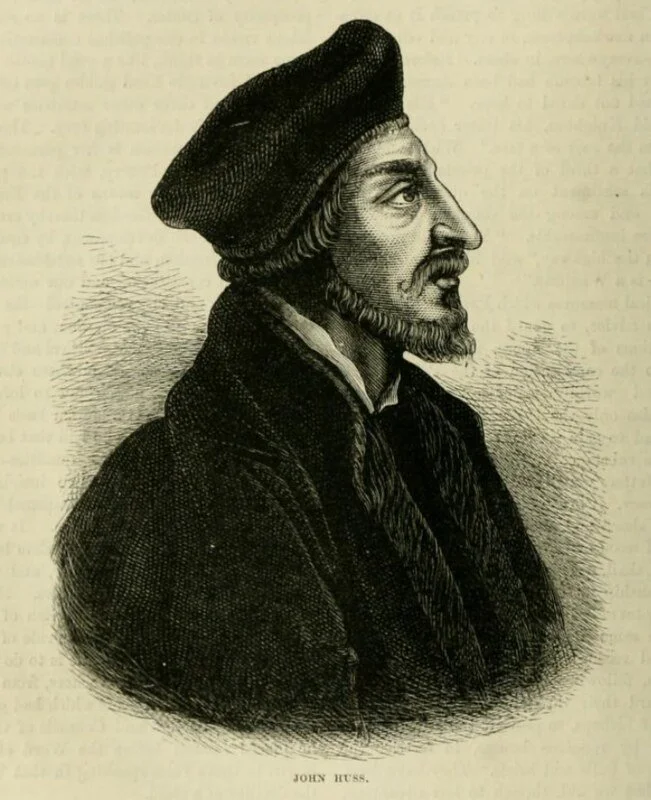

Emperor Charles IV himself ensured the safety of his land and merchants, leading armies in going after robber-knights and executing them. After the death of Charles IV, religious divisions emerged when the Bohemian priest and reformer Jan Hus, inspired by John Wycliffe's teachings (which were deemed heretical), began a reformation movement within the Catholic Church. Eventually, Huss himself would also be considered a heretic and executed by the Catholic church, leading to mass outrage from the Czechs. They saw their land as the model Christian kingdom and saw Huss’s prosecution as blasphemy. This would ignite a series of religious conflicts that challenged the universal authority of the Catholic Church as an institution, contributing to a centuries long schism between East and West.

Relief depicting Roman Emperor Charles IV. This is part of the west facade of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

Hussite Wars (Jan Žižka and military innovations) (Jul 30, 1419 – May 30, 1434)

Sources:

Britannica Editors. “Jan, Count Žižka.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 7 Oct. 2025, www.britannica.com/biography/Jan-Count-Zizka.

Buc, Philippe. “Medieval European Civil Wars: Local and Proto-National Identities of Toulousains, Parisians, and Prague Czechs.” War and Collective Identities in the Middle Ages, 2023, pp. 129–52, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781802701067.008.

Holmes, Robert C. L. "What we Learned from ... the 1419-34 Hussite Wars." Military History, vol. 38, no. 5, Jan., 2022, pp. 20. ProQuest, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.uh.edu/magazines/what-we-learned-1419-34-hussite-wars/docview/2600353169/se-2.

Kotecki, Radosław, et al. Christianity and War in Medieval East Central Europe and Scandinavia. New edition, Arc Humanities Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781641891349.

Lyons, Chuck. “Hussite Hand Cannons: A Revolution in Gunpowder Warfare.” Military Heritage, Apr. 2010, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/hussite-hand-cannons-a-revolution-in-gunpowder-warfare/. Accessed 2025.

Monroe, W. S. Bohemia and the Čechs : The History, People, Institutions, and the Geography of the Kingdom, Together with Accounts of Moravia and Silesia / by Will S. Monroe. G. Bell, 1918, 1918, pp. 50-106.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948. (40-48)

“King Wenceslas IV.” Radio Prague International, 7 Aug. 2002, english.radio.cz/king-wenceslas-iv-8064645.

Images:

“Blaschke Portrait of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor 1809” by János Blaschke (1770–1833), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Husitské zbraně” by Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

“Reformation - John Huss Portrait” by History Maps , Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“Wagenburg” by Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

This was a series of religious conflicts that were also named the Bohemian Wars, or more commonly known as the Hussite Revolution. The Hussite loyalists became outraged after their leader Jan Huss was burned at the stake on July 6, 1415. Their views were deemed heretical and blasphemous by the Catholic Church, supported by the Holy Roman Empire. They demanded the freedom to practice their religion and established the Four Articles of Prague. Utraquism was one of these principal beliefs, and was based around the belief that communion should not be limited to church clergy, but should be enforced to all worshippers. Followers of Huss would go on to view themselves as holy warriors in the service of God, known as Boží bojovníci. Huss became a martyr that fueled the Hussites' hatred of the Catholic Church. This sparked a social and national revolution that served as a proto-Protestant movement, spreading far beyond Bohemia and Moravia.

A portrait of Bohemian priest Jan Huss, also known as John Huss.

This ideological splinter began during Charles IV’s reign. His religious reforms proved controversial within the clergy, with the Germans holding conservative views of Catholicism, while the Bohemians leaned toward more progressive forms of Christianity. Emperor Charles IV’s son, Wenceslas IV, had far less tact with his administration, earning the ire of German and Bohemian nobility. Only ruling for a short period, he was born in February 1361 and crowned in 1378. While being given a world-class education and the training expected for an heir, he held habits such as excessive drinking and hunting considered unfit for his position. Emperor Wenceslas IV would be forced into an uncomfortable position with the Catholic church and the Czech nobility. He would be forcibly deposed as King of the Romans and King of Bohemia in 1400 by Bohemian officials after repeated imprisonment. His decision to poison St. John of Nepomuk, who was later canonized by the Catholic Church, also led to permanent damage to his relations with Church officials.

Hoping to salvage his reputation, he forged a political alliance with Jan Huss in 1402, and they maintained mutual support for nine years. This fell apart with the ascension of his brother, King Sigismund of Luxembourg, to the Roman throne in 1411. Far more capable as a ruler and with experience ruling Hungary and other lands, King Sigisumund initially guaranteed safety to Jan Huss, but backed out as Huss went on trial, with Wenceslas IV not intervening. He would shortly pass away from a stroke two weeks after priest Jan Zelivsky and some of his supporters led a protest in Prague. In defiance of the Holy Roman Empire, they marched to town hall on July 30th, 1419, and proceeded to throw several members of the municipal council out the window. This would be known as the first “Defenestration of Prague”, and would ignite the Hussite Wars.

King Sigismund succeeded his brother as Roman emperor, with his brother having no urgency to appease the rebels. In response to the rising threat of insurgency from Hussite revolutionaries, Emperor Sigismund sought the Pope Martin V to assist with the rebellion in 1419. They would go on to launch several Crusades against the Bohemian Hussites, whose existence threatened the dominance of the Catholic Church.

An 1809 portrait of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor.

Taking a stand against the invading crusader forces had impacted the identity of the Czech people well into the Thirty Years' War. A religious army began forming in the new town of Tabor, with allies in Prague, its university, and supporters from nationalities across the world. The majority of these Hussite combatants were common peasants who, lacking formal military training as soldiers or knights, took up arms . This was despite them being vastly outnumbered and out-resourced by the Holy Roman armies. Regardless, Hussites initially overwhelmed the crusading forces, first defeating them at the Hill of Vitkov outside of Prague, and again beneath Vysehrad. The success was largely thanks to the military prowess of Hussite revolutionary leaders.

The Hussites utilized various weaponry, ranging from swords, maces and spears, to ranged weapons like crossbows and new firearms. They even used farm equipment when needed as makeshift weapons.

This strategy was supplemented by the introduction of early firearms technology. The Hussites were the first to use portable firearms (hand cannons) in European battlefields.

Jan Žižka z Trocnova a Kalicha, who notably repelled crusaders near Kutná Hora, emerged as one of their most significant figures. Also known as the “One-eyed General”, he was an experienced military strategist, with his army organized effectively so that all units would work as a singular force. Taking advantage of the familiar terrain, Žižka was able to deploy unconventional military tactics, serving as an early example of guerilla warfare and asymmetric engagement. When there wasn’t enough traditional medieval weaponry, peasant equipment and farm tools were repurposed.

Another innovative element of warfare was the adoption of wagons for offensive purposes.

This is a 15th century sketch. The Hussites transformed farming wagons into makeshift mobile fortresses, known as Wagenburgs. Its armor provided defense while bolstering superior firepower. This gave them an advantage by wearing down enemy lines and breaking their formation.

Eventually, the Hussites switched back to defensive tactics after Zizka’s death, with cleric Procopius the Bald leading the charge all the way to the Baltics. The Taborites, who acted as representatives for the Hussites, decided to end the conflict to prevent further casualties. This was influenced mainly by the Hussites’ military defeat at the Battle of Lipany on May 30, 1434.

This was all the while acknowledging the rising pleas for peace from Bohemian citizens, with the Hussite Wars ending with all factions negotiating at the signing of the Basel Compacts in 1436. This agreement in the Basel Council allowed for religious tolerance for the Utraquists, with the Hussites eventually reforming themselves as the Unity of the Brethren, also known as the Church of Moravia.

Impacts of religious conflicts

Sources:

Crankshaw, Edward. The Habsburgs: Portrait of a Dynasty. 1971. The Viking Press, 1 Jan. 1972, 111-129.

Kotecki, Radosław, et al. Christianity and War in Medieval East Central Europe and Scandinavia. New edition, Arc Humanities Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781641891349.

Monroe, W. S. Bohemia and the Čechs : The History, People, Institutions, and the Geography of the Kingdom, Together with Accounts of Moravia and Silesia / by Will S. Monroe. G. Bell, 1918, pp.50-106.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948. (49-54)

Images:

The Compacts of Basle (based on the Four Articles of Prague) were adopted and accepted by Emperor Sigismund, who was once again recognized as King of Bohemia as part of the agreement. Many died from the Hussite Revolution, and much of the land was devastated by the wars, leading to a resurgence of German colonization. The Kingdom of Bohemia was eventually absorbed into the Archduchy of Austria by the Habsburg house in 1526. They succeeded the Luxembourg family’s reign over Bohemia after the death of King Sigismund. Austria, Hungary, and Bohemia would appoint Emperor Albert of Habsburg (1404-39), his son-in-law, after his marriage to Elizabeth of Luxembourg. Tensions from the Hussite party persisted before Albert died an early death, and his son, Ladislaus Posthumus (r. 1440-52), was accepted as king. This short-lived union between nations collapsed with Albert’s death, as conflicts over succession began. The Empire was split between Posthumus’ legitimacy and the desire for the sovereignty of King Vladislav, ruler of Poland. Hungary remained fractured after Vladislav died in 1444. The Hussite party was under the direction of George of Poděbrady (r. 1458-71), a nobleman who sought to reunify the nation and relinquish independence from the Catholic church. His actions made him an important figurehead in the future Protestant movement. After capturing Prague in 1448, he was placed in charge of administering all of Bohemia and regent of Ladislaus. Ladislaus died in 1457 of Leukemia, and George succeeded him as King.

Although he was a Hussite, he made attempts at reconciliation between Catholics and Utraquists. He also restored the old royal authority of Bohemia, with neighboring countries quickly establishing diplomatic relations with the king. His actions led to prosperity and growing Bohemian influence in Europe. Amid this reconciliation, however, was a growing concern over the Turks and their aggressive expansionism. King George was ready to utilize Czech military power. An alliance between Christian kings was proposed by George in 1462. And while he faced Papal opposition for his refusal to relinquish his Protestant faith, he was able to secure an alliance with France after sending his ally, Pius II, claiming denial of the Basle Compacts. This created religious controversy, and after Pius II’s death, King George faced a German rebellion supported by his son-in-law Matthias Corvinus, tensions from the Papacy, and the lingering Turkish armies. He would soon die in 1471, with the reign of the Luxemburgs falling alongside him. Soon after, the Kingdom of Bohemia was taken over by King Vladislav of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Poland, following the death of Matthias in 1490. George’s influence remained as the belief of the separation of worship and political rulership had begun to spread. This would be carried on by the Jagiellonian dynasty under Vladislav and his son, Louis.

Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648)

The Thirty Years’ War was sparked in multiple phases by the Protestant Bohemian nobility's rebellion against the Catholic Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II. Although the Hussites secured their right to religious worship outside of Catholicism following the Compacts, Bohemia would be invaded by King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. He was officially accepted as king by the Czech Catholic Estates, but many Bohemians remained loyal to George of Poděbrady (r. 1458-71). The religious doctrine of the Catholic Church and the Hussites were then ratified as equal with the Religious Peace of Kutná Hora in 1485. By the 1600s, however, the Catholic church sought to banish all non-Catholic faith practices, sparking a new series of religious rebellions, now led by Protestant forces. Under the Spanish Habsburgs, Bohemia had become subjugated by Ferdinand II, whose religious fanaticism began to eat away at the religious rights of Protestant factions.

War ignited in the aftermath of religious infighting over the “ Letter of Majesty”, with arguments over what was considered to be royal domains permissible to establish Protestantism, with many churches being demolished. War broke out as Ferdinand II, aided by Maiamillian of Bavaria, had sought to vanquish the proclaimed “heretical” forces of Bohemia led by King Frederick. Bohemia organized a standing army and a temporary government in 1618 while expelling all Jesuit Catholics. By 1620, the Czech Protestant forces were without allies and faced overwhelming opposition from the Holy Roman Empire. The Bohemian estates would suffer a fatal defeat in mere hours by the Central European Catholic forces at the Battle of White Mountain. Victory and the resulting occupation of Bohemia were swift, with those amongst the nobility who had not fled after White Mountain being executed. Bohemia lost its sovereignty and was depopulated from around 4 million to about 800,000. Bohemia was subsequently absorbed into the Habsburg empire, losing its independence in 1648 following the death of Ferdinand II and his succession by his son Ferdinand III (r. 1637-57) with little autonomy until the outbreak of the Great War.

II. Habsburg Era (1526–1918)

Jagiellonian control over Bohemia was compromised with the death of King Louis, and a successor was chosen from the Habsburg family. Ferdinand I (r. 1526-64), a Habsburg noble and husband of Jagiellonian princess Ann, would be crowned as King of Bohemia along with Hungary, with his rulership instituting his family’s reign over the Czech and Slovak people for four centuries. Although initially popular with Hussities, this would sour between the tolerant Estates and his new administration, closely allied with the King of England, Henry VII, and the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by his brother Charles V. Son of Maximilian I, Charles inherited his father’s dynasty, built on a failing medieval system of rulership. He would rise from poverty to riches all across Europe and even the Americas. He was amicable with his older brother Ferdinand, but his son Philip would begin having power struggles with Maximilian II, son of Ferdinand II. His biggest struggle, however, would be his attempts at forming a Catholic religious and political order amid the progression of religious movements led by figures such as Martin Luther.

By 1517, Martin Luther had already kick-started a similar religious reform movement in Germany, with his reformation movement being well received amongst the Czech Utraquists. King Ferdinand I himself was struggling with religious upheaval in Germany between the Roman Catholics, who represented a third of Bohemia and Moravia, the Bohemian Unity of the Brethren, the Hussite Utraquists, and the Lutheran Protestants. When Charles V was crowned to lead the Holy Roman Empire in 1521, he had to address the empire’s waning influence along with the imminent Turkish threat of invasion. During his reign, he struggled to unify Christendom, even meeting Luther to discuss these matters, but to no avail. Despite agreeing that reform in the church was overdue, Charles V refused to delegitimize the Catholic church. Although it placed a ban on Luther’s teachings, this would prove insufficient. King Henry VIII of England distanced himself from Catholic teachings to establish his own church, and Lutheranism continued to spread. He would resign from his position in 1556, with his brother taking over the empire. While both failed to halt the spread of Protestantism, Ferdinand established his legitimacy with approval from the Estates. Ferdinand II called for the establishment of a Catholic-led council to hinder the influence of the Brethren and the Lutherans, although it was dismissed by the Romans. Many Czechs by the 1540s had sided with the Lutherans and paid a heavy price, with Czech members of the Brethren being tortured, their property confiscated, and prosecuted, although this did not stop their growth.

After Ferdinand II succeeded his brother Charles V as King of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire for 8 years, his son became an arbiter of the Catholic faith. Maximillian II (r. 1564-76) promoted appeasement over force and was tolerant of the Lutheran and the Brethren. His successor Emperor Rudolf II (r. 1575-1608/11), also adopted Protestantism later during his reign, as Europe had become split between the Protestant North and Catholic South. He focused more on the arts and sciences than rulership, and decreed Prague as the new capital. One of more notable moments was in 1609, where he declared religious tolerance and freedom for his Protestant subjects, much to the fury of the Catholic party.

Disposed from his failure to diminish the spread of Protestantism, Rudolf II was deposed and replaced by Emperor Matthias (r. 1612-19), who was much more aligned with the Catholic party’s anti reformationist ideals. His older age meant a short reign, but his rule marked the end of Bohemian sovereignty. Nations became split between religious ideology, with Czech schools and society hindered under the Habsburg crown. Anti-Habsburg sentiments grew, and Matthias was soon replaced by the fanatical Ferdinand II, whose reign would bring about the horrific Thirty Years War and the end of Bohemia as an independent Kingdom. King Ferdinand II of the Spanish Habsburgs sought to centralize power and establish a Catholic theocracy. Bohemia faced interference in previously agreed-upon agreements to allow the establishment of Protestant churches. The war ended with the loss of independence for Bohemia after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, although fighting continued as proclaimed King Frederick refused to back down. By 1622, he was ready with around 40,000 men to retaliate.

Wallenstein rejected offers from the Protestant forces and fought alongside the Imperial forces. He amassed wealth and a personal army by 1625 after his victories at White Mountain and in subsequent battles. This Czech-born officer would help defeat the remaining Protestant forces, although he would later be assassinated in 1634. Ferdinand II himself would pass away in 1637, with his son Ferdinand III being crowned, and the war ending by 1648.

Czech soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian military

Sources:

Crankshaw, Edward. The Habsburgs: Portrait of a Dynasty. 1971. The Viking Press, 1 Jan. 1972, 57-257.

Davies, Brian L. Warfare in Eastern Europe, 1500-1800. Brill, 2012, 35-61, 199-248.

Monroe, W. S. Bohemia and the Čechs : The History, People, Institutions, and the Geography of the Kingdom, Together with Accounts of Moravia and Silesia / by Will S. Monroe. G. Bell, 1918, pp.107-155.

Mutschlechner, Martin. “The Czechs in the Habsburg Monarchy.” Der Erste Weltkrieg, 17 Aug. 2014, ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/czechs-habsburg-monarchy.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948. (55-103)

Stone, Norman. “Army and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1900-1914.” Past & Present, no. 33, 1966, pp. 95–111. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/649804. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Tracy, James D. Balkan Wars: Habsburg Croatia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Venetian Dalmatia, 1499-1617. 1st ed., The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2016. (135-43, 186-190, 271-276, 324-329, 361-366 for direct involvement of Bohemia)

Watson, Alexander. “Managing an ‘Army of Peoples’: Identity, Command and Performance in the Habsburg Officer Corps, 1914–1918.” Contemporary European History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2016, pp. 233–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26294099. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Images:

The people of Bohemia made up the third largest ethnic group in the Habsburg monarchy, with Bohemia spanning the lands of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia. They held deep rivalries with the German-speaking peoples of Austria and Germany, even in the military. It was significant to the industrial capabilities of the Habsburg monarchy, and around 6.7 million had declared themselves of Czech origin by 1910. They formed a significant portion of the Habsburg armed forces and served in several armed conflicts across Europe and Western Asia. The 1500s and onwards saw the modernization of warfare from medieval weaponry such as swords and spears, and troop positioning towards wheellock firearms, naval combat, artillery, and the retirement of plate armor. Hajduks were armed men ranging from freedom fighters to bandits, with Czech, Slovak, and other ethnic groups becoming hajduks. They were known for their involvement in fighting off Ottoman troops from repeated military invasions.

By the early 1900s, Czechs in the military of the Habsburg Monarchy were amongst a diverse cast of armed forces within the Common Army, with posters often displaying translations for up to 15 languages. The officer corps meanwhile was composed mainly of Germanic officers, with Czech officers needing to become bilingual in German and being far rarer in comparison. Reserves from middle-class populations were typically German, while Czechs and Slovaks made up lower-class reserve units. Making up 17% of the population in total, Czechs made 12.9% of all recruits and Slovaks 3.6%. Meanwhile, Czechs were less than 5% of active officers and 9.7% on reserve, and Slovaks were not given any officer positions, with less than a percent officially on reserve. This was only permitted as the Habsburg army was in need of educated men, as they held distrust of the Czech reserves over a rising nationalist movement. In the later years of the Great War, Slavic groups such as the Slovaks were permitted to become reserve officers.

The army itself was seen as the most stable element of the monarchy, as the Austria-Hungarian Empire was on the verge of internal collapse by 1918. Habsburg war efforts were led by the Imperial and Royal War Ministry. However, the army faced numerous crises including a lack of funding, waning firearms production compared to other nations (with the Habsburg military seeing their production budget less than doubled, while nations such as Russia had more than tripled theirs), and only half of adult males being properly trained for combat. Breakdowns in communication amongst the reserve officers occurred over linguistic issues, as many only spoke their native tongue in an army of many ethnicities and nationalities. This led to incidents from non-German-speaking civilians, including Czech ethnic civilians.

Czech military identity under imperial rule

Sources:

Borchardt, Karl. “National Rivalry among Hospitallers?: The Case of Bohemia and Austria, 1392-1555.” Medievalista on Line, no. 30, 2021, pp. 203–45, https://doi.org/10.4000/medievalista.4535

Mutschlechner, Martin. “The Lack of Alternatives: The Attitude of the Czechs towards the Habsburg Monarchy at the Outbreak of the War.” Der Erste Weltkrieg, 17 Aug. 2014, ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/lack-alternatives-attitude-czechs-towards-habsburg-monarchy-outbreak-war.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948. (55-103)

Stone, Norman. “Army and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1900-1914.” Past & Present, no. 33, 1966, pp. 95–111. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/649804. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Watson, Alexander. “Managing an ‘Army of Peoples’: Identity, Command and Performance in the Habsburg Officer Corps, 1914–1918.” Contemporary European History, vol. 25, no. 2, 2016, pp. 233–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26294099. Accessed 25 June 2025.

Images:

While the Czechs felt protected by the power of the Habsburg empire, they also perceived themselves as captive, lacking the right to self-determination as a sovereign state. Although they reluctantly declared fealty to the empire, by 1914, discontent was present amongst civilians. Although there were no large-scale rebellions initially, as feared, there was also no love for the Habsburg Empire’s militaristic goals, with sympathy even being given to their Slavic neighbors who were allied with the Entente forces.

The Knights Hospitaller order, a military organization under the authority of the Catholic Church, showcased that tensions existed between military personnel even before the administrative takeover of the Kingdom of Bohemia. The Hospitaller order separated itself into langues or “tongues” based on ethnicity rather than national origin, with 8 tongues being established by 1462. Bohemia and Austria were one priory and under the Holy Roman Empire tongue, but Bohemian Hospitallers retained their Czech language and cultural identity. This organization did not abide by political rivalries or borders, but rather simply followed geographical and organization lines. This led to confrontations within Bohemia’s priory as several ethnicities and languages were forced under one organization.

This was demonstrated when Fr. Johann Schenk, Lieutenant for Austria, and Fr. Otto Lembucher, Commander of Mailberg, faced a severe dispute that escalated to violence and extortion, with Lembucher being backed by Duke Albert III of Austria. Schenk was under the command of the Bohemian prior, with the Bohemian kings and dukes of Austria, who sought to challenge Bohemian oversight using the Hospitaller order for their political games. To avoid risking further escalation, the Bohemian avoided condemning Albert, much to their chagrin. This relationship was further complicated following the Hussite Revolutions and the rise of the Habsburg dynasty, with the Bohemian prior conflicting with the directives of the papacy and the Habsburg imperials. Although the Hussite wars severely weakened the standing of the Bohemian Hospitallers in the Catholic church, the church decided that embracing them under their umbrella was preferable following the Thirty Years' War.

Support for the deployment of the Habsburgs’ Common Army was widespread initially. But by 1916, the Czechs and other groups, seen as subservient to the Germans and Austrians, began questioning the monarchy. Although the Common Army in WWI was designed to imbue loyalty towards imperial rule, it was segmented by nationalistic differences. Many struggled over the necessity of speaking German, with a version of German mixed with Slavic influences being used to communicate with troops. Suspicions were rampant over strife amongst the Czech people, leading to suspicions of an expanding nationalist movement that threatened the Habsburgs’ authority. Much of these suspicions were arguably misattributed to nationalism rather than resentments over the decision making of the military leadership. Regardless, there were examples of internal dissonance and desertion, such as when the Habsburg army faced an internal conspiracy to undermine the army led by Ljudevit Pivko in 1917, with Czech officers being amongst the conspirators. Outbreaks of violence and anti-imperial revolts occurred from civilians and soldiers over increasing resentments over Germanic and Austrian favoritism from the Habsburg leadership, along with rising anti-war sentiments. Tensions regarding Czech and Slovak units were further strained as thousands of prisoners joined the Imperial Russian army as part of the Czechoslovak Legion against the Habsburg monarchy.

Major conflicts: Ottoman wars, Napoleonic Wars

Sources:

Baugh, Daniel A. The Global Seven Years War, 1754-1763 : Britain and France in a Great Power Contest. Second edition., Routledge, 2021.

Bennett, Mark. “International Analysis of Battlefield Performance in the Austro-Prussian War, 1866-1870.” War & Society, vol. 41, no. 3, 2022, pp. 182–200, https://doi.org/10.1080/07292473.2022.2087399.

Crankshaw, Edward. The Habsburgs: Portrait of a Dynasty. 1971. The Viking Press, 1 Jan. 1972, 131-227.

Damjanovic, Dragan. “Building the Frontier of the Habsburg Empire: Viennese Authorities and the Architecture of Croatian-Slavonian Military Frontier Towns, 1780–1881.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 78, no. 2, 2019, pp. 187–207, https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2019.78.2.187.

Davies, Brian L. Warfare in Eastern Europe, 1500-1800. Brill, 2012. (35-61, 199-248)

Embree, Michael. Too Little, Too Late : The Campaign in West and South Germany, June-July 1866. Helion & Company, 2015.

Britannica Editors. "Napoleonic Wars". Encyclopedia Britannica, 24 Sep. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Napoleonic-Wars. Accessed 6 November 2025.

Finkel, C. F. “French Mercenaries in the Habsburg-Ottoman War of 1593–1606: The Desertion of the Papa Garrison to the Ottomans in 1600.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 55, no. 3, 1992, pp. 451–71, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0041977X00003657.

Finlay, George. A History of Greece, from Its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time, B.C. 146 to A.D. 1864; by George Finlay, LL. D : V.6. Clarendon press, 1877, 1877.

Fisher, Todd. The Napoleonic Wars The Empires Fight Back 1808–1812. 1st ed., Osprey Publishing is part of the Osprey Group, 2001, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472895462.

Hochedlinger, Michael. Austria’s Wars of Emergence : War, State and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1683-1797. Routledge, 2013.

Palffy, Geza. “Liberation or Occupation? Military, Financial, and Civil Administration in Recaptured Hungary during the Great Turkish War, 1683-1699.” Historický Časopis, vol. 70, no. 4, 2023, pp. 581–608, https://doi.org/10.31577/histcaso.2022.70.4.1.

Pálffy, Géza. “The Habsburg Defense System in Hungary Against the Ottomans in the Sixteenth Century: A Catalyst of Military Development in Central Europe.” History of Warfare, vol. 72, BRILL, 2012, pp. 35–61, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004221987_004.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Persson, Mathias. “Mediating the Enemy: Prussian Representations of Austria, France and Sweden during the Seven Years War.” German History, vol. 32, no. 2, 2014, pp. 181–200, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghu036.

Pike, John. “The Habsburg Military.” GlobalSecurity, 23 May 2019, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/at-kuk-heer.htm.

Polišenský, Josef V. History of Czechoslovakia in Outline. Sphinx Publishers, 1948. (55-103)

Tracy, James D. Balkan Wars: Habsburg Croatia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Venetian Dalmatia, 1499-1617. 1st ed., The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2016. (135-43, 186-190, 271-276, 324-329, 361-366 for direct involvement of Bohemia)

Tracy, James D. Balkan Wars : Habsburg Croatia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Venetian Dalmatia, 1499-1617. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Vardy, Nicholas A., Barany, George, Várdy, Steven Béla, Macartney, Carlile Aylmer. "History of Hungary". Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 Mar. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Hungary. Accessed 6 November 2025.

Wawro, Geoffrey. The Austro-Prussian War : Austria’s War with Prussia and Italy in 1866. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Zuber, Christina I. “Imperial Borderlands: Institutions and Legacies of the Habsburg Military Frontier. By Bogdan G. Popescu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024. 317p.” Perspectives on Politics, 2025, pp. 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592725000908.

“The War of the Spanish Succession: First World War of Modern Times.” The Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum, 14 Nov. 2022, www.royalhampshireregiment.org/about-the-museum/timeline/war-spanish-succession/.

“War of the Spanish Succession.” National Army Museum, www.nam.ac.uk/explore/spanish-succession. Accessed 13 Aug. 2025.

“War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14).” Royal Collection Trust, militarymaps.rct.uk/war-of-the-spanish-succession-1701-14. Accessed 13 Aug. 2025.

Images:

“Bohemian - Archer's Shield - Walters 511371” by Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Czechs and Slovaks would participate in many wars and conflicts throughout the reign of the Habsburg dynasty:

The Ottoman Wars (1439-1526, 1526-1791)

Bohemia was involved in the Hungarian–Ottoman Wars (1439-1526) when the Ottoman Empire gained significant ground in the mid 1400s, with Constantinople ( a city representing the division of Asia and Europe) under their control in 1453, followed by Serbia and Bosnia in the 1460s.They outmatched Habsburg-controlled-Hungary in territory, populace, resources, and armed units. While border clashes between the two empires broke out into the 1500s, the ruling Sultan would make his move to conquer their neighbor by 1521. Classic medieval defense systems were no longer sufficient for defense, with the army of Sultan Suleyman threatening the reign of Bohemian and Hungarian-Croatian ruler Louis II Jagiello of the Jagellian dynasty. Their victory at the Battle of Mohacs on August 29, 1526 was curtailed however by the rise of the Habsburg dynasty, with the new leadership reforming their defense strategy to counter future invasion. Under the rule of the Habsburg house, Bohemia and the rest of the empire would see itself involved in a series of territorial conflicts and border disputes from 16th to 18th century Europe, now known as the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars.

Late Medieval Archer’s Shields (Mid-15th Century)

Following the crowning of Ferdinand, the Sultan laid siege to Vienna on 27 September 1529, and although his numbers far exceeded Ferdinand I’s standing army, they lost much of their siege cannons during their trek to Vienna, with the Ottoman army eventually retreating after much resistance. Taking advantage of this blunder, Hungary and the Habsburgs sought to establish a militarized borderland to the southeast known as the military frontier established as Ferdinand I was well aware of the Sultan’s burning desire to snatch control over Vienna, capital of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Lacking a clear military policy until the late 1540s, they settled on keeping Ottoman forces at bay in Croatia and Hungary. This changed with the fall of the capital of Hungary, Buda, on August 29, 1541. Further losses from a failed attempt to reclaim the empire would see the military frontier established far nearer to the Austrian border by 1543. Although Vienna was under further threat, natural features along with reinforced and new castles bolstered the border system. Sultan Suleyman would sign a treaty 2 years later, with Hungary being split. His occupation continued until 1568, however, as he did not give up on his goals of conquering Vienna, with Hungary becoming the dividing line that kept the Ottoman Empire out of Central Europe.

The Military Frontier

New considerations for border policy of Hungary commenced in the later 1550s within Vienna and Pozsony, where several factors were discussed in creating defense zones around Croatia and Hungary. The Habsburg territories of Austria and Bohemia ended up carrying Hungary’s financial burden for its defense. The Aulic War Council starting in 1556 convened on creating a universal defense strategy, with a need for experienced soldiers and officers to counter the Ottomans. Eventually by 1560 this border extended all the way from the Adriatic Sea and toward the Transylvanian and was composed of 100-120 fortresses. The main fortresses could carry a garrison of between 1,000-1,500 men, with secondary fortresses carrying 400-600 and the smallest 100-300. These fortresses were assigned into 6 defense zones led by captains with one central fortress, Komarom in Danube, being the center of defense operations for Vienna. This was reinforced with a new flotilla of naval ships along with castles of 300-500 men along the Croatian and Slovenian borders. The military frontier was finally established as a dual organization whose leadership was split between the Border Fortress Captain Generalcy, whose authority was derived from the Aulic War Council, and the District Captain Generalcy, whose powers were owed to the nobility.

This system would remain as is until 1577, when it was decided that the fortress border plan needed to be reexamined and modernized. Flaws were examined at an August military conference along with opportunities for offensive strategies against inevitable raids by the Ottomans, who had been gathering military intelligence over the years. Internal debate about whether to adopt an active defense strategy or to use the armored border to strike first went on, as while the Chrisitan forces held superior firearms technology revamped military tactics, taking consideration of the need for funding (which was already strained in funding the military frontier), logistical shortcomings in the Habsburg army, and the need to maintain diplomatic relations meant that a conservative approach was deemed more feasible. The Border Captain Generalcies were reorganized into new defense zones that better utilized the terrain, creating natural barriers through flooding, demolishing forests, and creating hazards that would impede invaders. Old castles and fortifications were renovated into modern fortress cities, with some having architectural influences from fortresses in Italy for example. The inner Austrian noble estates were handed over the southern Croatian and Slovenian border generalcies by the Aulic Council as a means of centralization and covering potential flanking risk, with the estates forming the Inner Austrian War Council in January 1578. Lastly consideration was given to improving fortress resupply operations led by the Chief Arsenal Officer, along with a suggested reorganization of the border defense administration, with many of the proposed reforms established by the 1580s.

Thirteen Years' War (1593–1606)

Also referred to as the Long Turkish War, it would be initiated in 1593 by the King of Bohemia and Roman Emperor Rudolf II (r. 1576-1612) in his attempts to establish Christian dominance, with the war later showcasing that restraint and defense was the optimal move in waging war against the Ottoman army. Although by the 1590s the Ottoman Janissary units had begun adopting musket volley tactics and new weapons technology, the Sultan, Murad III, had ascended to the throne in 1574 and was seen then as an insufficient leader with promiscuous habits. The Habsburgs meanwhile had undergone a series of military reformations over the last few decades that had allowed the Empire to repel repeated assaults, with 20,000 military personnel ready at the Hungarian-Croatian military frontier and whose numbers surpassed any other standing army in Europe. The Ottomans, however, had major military successes capturing cities and fortresses such as Bihac in 1593, Eger in 1596, and Kanizsa in 1600. This was likely due to the administrative and financial structures of the Habsburg Monarchy, as they still had far fewer resources and territory, and were nowhere near as experienced in siege warfare. Their total military forces still soared above Vienna’s military and they even had the advantage of having created a sophisticated resupply-chain system. The Habsburgs meanwhile had most of their army garrisoned at the border fortresses, and relied on financial support from their allies. Although Vienna and the Habsburg Empire technically won the war, it was only after losing significant territory and supplementing their forces with allied Habsburg units, ending with the 1606 Treaty of Zsitvatorok and the threat of occupation still looming, eventually leading to future conflicts such as the Great Turkish War.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

The Spanish Empire was in outright turmoil following the death of Charles II of Spain in November 1700. Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I was pulled into a war started by his father, Emperor Leopold I, against King Louis XIV of France. A plot was formed to secure his older brother Charles as the future King of Spain, supported by Prussia, England, Holland, and the Holy Roman Empire, and later Portugal and Savoy by 1703 as part of the Grand Alliance. Fighting against the forces of Philip of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV of France, the war would last until 1714, with Philip of Anjou being recognized as the King of Spain with the passing of the Treaties of Utrecht in 1713, and both Rastatt and Baden in 1714.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748)

On April 17, 1711, Emperor Joseph I was infected with smallpox following an epidemic and amidst continued fighting over the Spanish crown. Newly throned Charles VI would then assume control of the Austrian territories including Bohemia and Moravia. His reign lacked any major conflict as the Austrian Habsburgs gained major territory in Italy and the Netherlands, although they would also cede some territories following losses to the Ottoman Empire. April 19, 1713 would see Charles VI enacting the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 to ensure that his daughter would be the rightful heir to the Habsburg hereditary lands. His death on October 20, 1740 was arguably his biggest mark on the Habsburg dynasty as it would spark a frenzy as without any male heirs, many would contest Charles’ daughter Maria Theresa’s right to the throne in what would become the War of the Austrian Succession.

Seven Years' War (1756-1763)

This massive 18th century military conflict stemmed initially between European and Asian powers that would later spill onto the Americas and elsewhere. Bohemia military units under the Habsburg Empire, ruled by Holy Roman Empress and Queen of Bohemia Maria Theresa (r. 1743-1780), would become involved with Austrian desires to regain control of the region of Silesia which was priorly lost to the Prussians under the reign of King Frederick the II of Prussia during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). Having inherited an army diminished by the loss of generals who were imprisoned for failing to fight off the Turks, along with a declining empire whose allies and neighbors were plotting to cut up and take for themselves, Queen Theresa faced challenges from her cousin Charles Albert of Bavaria, who sought the throne for himself, along with the King of Prussia Frederick II (r. 1740-86), who resented Queen Theresa’s crowning. He began a campaign in December 1740 that grew out of control and lasted decades. Having demolished the Austrian forces with about 30,000 Prussian troops, Theresa retaliated but found her freed generals waning in their leadership prowess, and her English allies reluctant to assist for fear of antagonizing Prussian ally France.

Despite this caution, French forces were already planning to take advantage of Austria's struggles led by general Belle-Isle. Although he had ambitious plans to carve out Austria, his plans were disrupted by Queen Theresa’s relentless pursuit to reclaim Silesia, and in failing that to drive out the French and Bavarian forces out of Vienna and Prague while retaliating against the Spaniards and French occupied Italy.. Requesting aid from the Hungarians, she would find herself losing Prague and later Silesia, with Charles Albert claiming himself king of Bohemia while losing the capital of Bavaria. By 1743, Queen Theresa had her coronation as Queen of Bohemia and believed that the war would be overwhelmingly won, but the fighting continued until the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. Prussia had control over Silesia under Frederick the Great and Queen Thresea realized she was in great need of new ministers and advisors for her military, new trainers and schools, as well as funding, pushing her to tax the wealthy estates which was a novel and controversial idea. She also believed that the peasantry could not be dismissed as disposable units, believing that an edge lied in looking for those with hidden potential to bolster her army. She assigned Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz with these reformations in mind as he implemented taxes for funding an army of 108,000 men, with men from many nationalities including Czech and Slovak peoples being assigned to serve the Habsburg crown over their respective nations. Additionally, chosen officers were reprioritized based on talents rather than noble blood status, with the army having gone through such a dramatic redesign.

Third Silesian War (1756-1763)

Determined to take back Silesia even without allied support, Queen Theresa and her advisors waited to take advantage of any mistakes, with England in 1756 making a deal with Prussia to protect Hanover amid security anxieties, angering both France and Russia in the process. The Habsburgs would find themselves allied with Russia and France against England, Prussia, and Holland. Defense treaties between nations would pull many factions into the fold as Theresa found her resilience against these invaders expanding into a multi-continental conflict. Although Austria never recovered Silesia, it came back as a more sound nation.

The Austrian-Habsburg forces saw their first major victory at the Battle of Kolin on June 1757 in Bohemia, with Habsburg commander Leopold Daun defeating Frederick the Great’s forces, and again in Hochkirch in the fall of 1758 with Daun being assisted by commanders Laudon and Lacy. Frederick lost once more fighting the Russians and Commander Laudon in 1759. This did not dissuade him however as the conflict continued and by 1761 France had exited the conflict and Russia in 1762, with Austria by itself and Queen Theresa regretting the conflict. The war would end with a stalemate with territories being returned to their pre-Seven Year War status with the Treaty of Hubertusburg in 1763.

Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815)

The Habsburg Monarchy was involved significantly in the Napoleonic Wars, mainly opposing Emperor of the French Napoleon and France’s militaristic ambitions except for a short alliance against Prussia, eventually leading to Napoleon's downfall. Bohemia remained supportive of Austria’s efforts in an official manner, although begrudgingly so. Spanning over multiple coalitions and campaigns, Austria would enter the fray with Francis II (r. 1792-1835), positioned as the last Holy Roman Emperor, the first Emperor of Austria in 1804, and the King of Bohemia. Following Austria’s defeat at the hands of the French army and General and later Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (r.1804-1814) during the French Revolutions and the War of the Second Coalition, which sought to contain the French Republic and preserve the legitimacy of monarch rulership, they would continue their conflict along with several European coalitions against the Empire of France.

Emperor Napoleon had previously used his military pressure to force the disbanding of the Holy Roman Empire with the 1806 Treaty of Pressburg. Francis II’s easy-going and lax personality was not conducive to leading a military campaign, and was dethroned and humiliated. Francis II in the aftermath would reconvene with various European powers with the help of his foreign minister, Prince von Metternich, who served as spy-master and directed Austrian politics. Austria itself was politically and militaristically isolated in 1805, only gaining more influence with Metternich’s ascension to office in Vienna in 1809 and Austria rejoining the conflict against Napoleon.

War of the Fifth Coalition (Apr 10 – Oct 14, 1809)

Emperor Napoleon’s forces had been waging war on European nations attempting to resist the expansion of a French Hegemony well into the early 1800s, with Habsburg controlled Austria managing to avoid the fighting until an opportunity arose. With Germany and Italy under the subjugation of France, the Habsburg monarchy sought to restore their territorial rights and expand their influence under the guise of resisting French imperialism by taking advantage of the French army’s defeats in Spain. Preparations began in late 1808 with cavalry, artillery, and army units were organized into army units, with tens of thousands of troops on horseback and several hundreds equipped with musket arms. Archduke Charles, brother of emperor Francis II, would lead the main offensive front with around 190,00 men against Napoleon's forces starting with a starting offensive in the French-controlled state of Bavaria, south of the Danube River, on April 9th, 1809. Smaller armies were assigned to Spain, northern Italy, and Croatia simultaneously to undermine Napoleon’s hold over these regions, with the Austro-Hungarian Army striking the French first. Initial success was found in routing Emperor Napoleon’s army and advancing past the Isar river in Bavaria towards French forces near the towns of Regensburg and Landshut. Despite early victories however, a counterattack was successfully launched by French forces led by Marshal Devout at the Battle of Eckmühl. Charles led a retreat towards Vienna, and by May had lost around 60,000 soldiers in his primary army.

In the wake of their defeat, other nations such as Prussia remained reluctant to support Austria’s ambitions against Napoleon’s forces. Charles and his army retreated into Bohemia while Emperor Napoleon moved towards Vienna with attempts to capitulate the capital, only to be postponed by sabotaged bridges and troops stationed at the Danube flank. Napoleon and his army of 180,000 strong then came into contact with Charle’s forces on May 20th, with heavy fighting breaking out over 2 days near the villages of Aspern and Essling in Austria. The Battle of Aspern-Essling seemingly turned the tides of the war towards the Habsburgs. With Napoleon retreating after losing 30,000 troops, and Charles around 23,000. Although seemingly a pyrrhic victory, Napoleon’s authority was successfully challenged and his military reputation stained, leading to a treaty being signed known as the Peace of Vienna in October, 1809 in order to prevent further escalation. Still, this victory came at a significant loss of territory as Emperor and king Francis II lost large swaths of his land and millions of citizens to France, ensuring that future conflict would arise.

War of the Sixth and Seventh Coalition (1812–1814, 1815)

Prince Metternich’s administration during the early 1800s was seen as overly oppressive by Bohemians, who feared persecution over questioning the Habsburg’s rulership. Metternich himself was stationed in France and worked to maintain peace between the Habsburgs and the French Empire, until relations began to collapse between France, the Prussians led by Frederick William III, and Russia led by Alexander I in 1812. Austria this time was obliged to assist Napoleon’s invasion campaign of Russia as per the Treaty of Paris signed earlier that year, with Metternich and Francis II seeking to gain political favor with France. The invasion began on June 24, 1812, with Austria supplying 30,000 troops to Emperor Napoleon. This would not last long as the invasion became an infamous disaster, with the Russian forces biddening their time in the winter, with the heavy snow becoming a war of attrition with Napoleon’s army against the elements. The extreme weather led to attempts at retreat, with hundreds of thousands being lost to frostbite or abandonment, with only 100,000 casualties being estimated to be from battle.

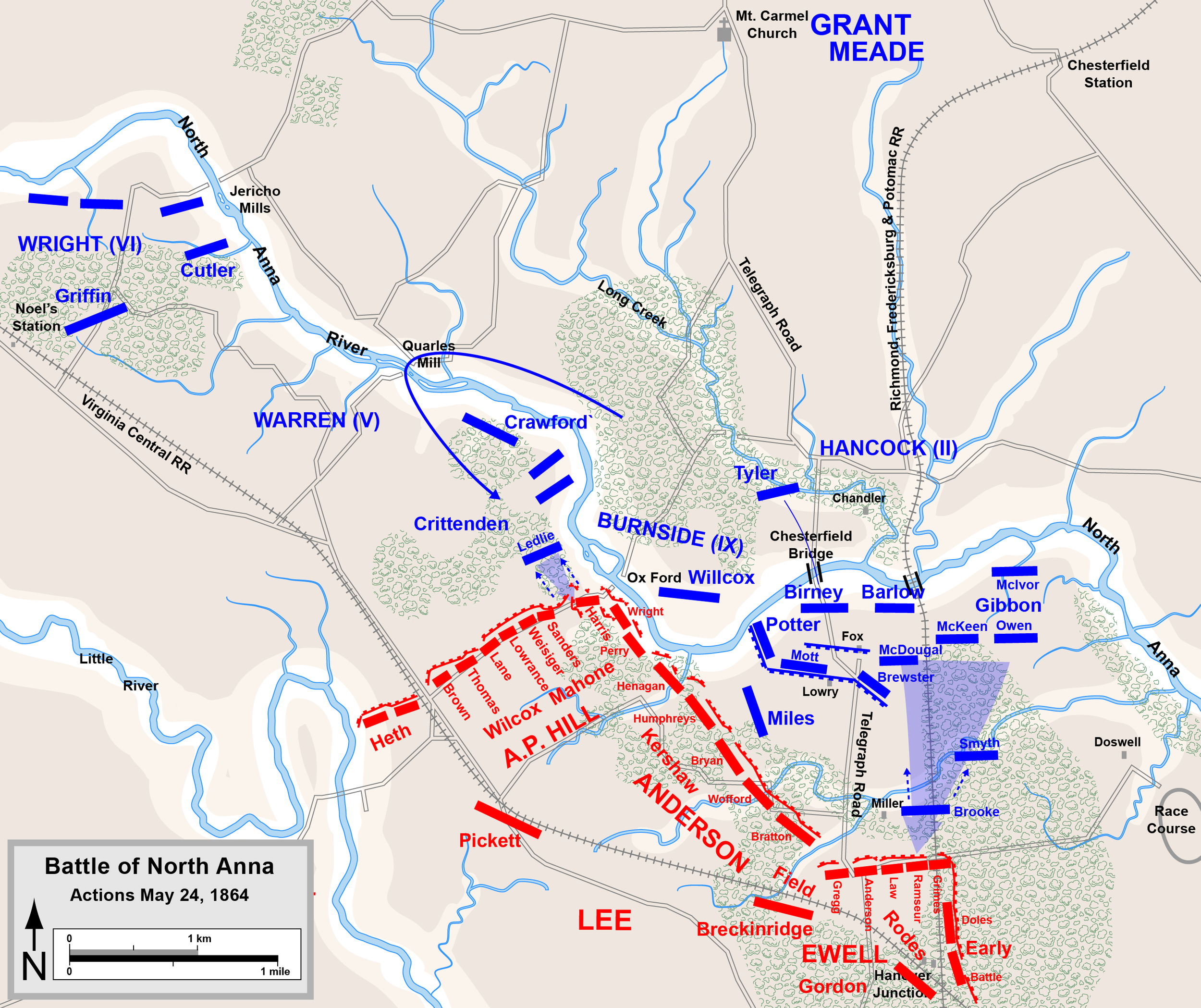

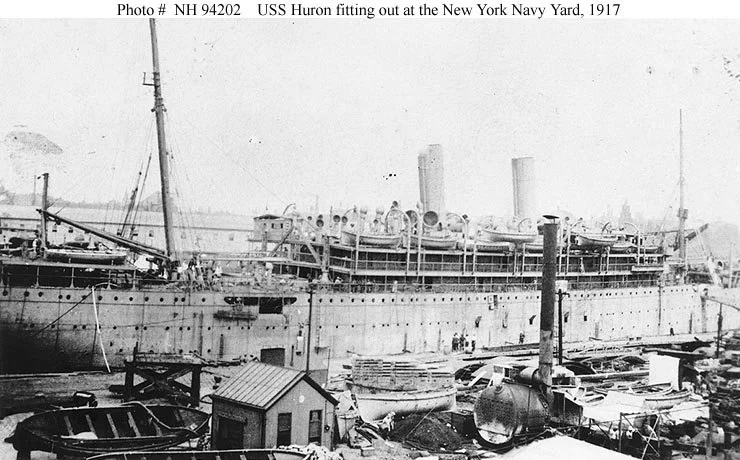

The disaster of the invasion attempt led Austria, Prussia and other nations in August 1813 to form a new alliance to abdicate France’s hold over Europe, with Napoleon’s failure to conquer Moscow becoming indicative of his future failures. Austria supplied a contingent of around 127,000 soldiers to the 6th coalition, forming the Army of Bohemia under Prince Schwarzenberg of Austria with assistance from Alexander I of Russia and Frederick William III’s Prussian forces, forming an eventual total of 250,000 men. This army’s contributions led to the loss of Dresden in Eastern Germany as allied forces converged towards France’s borders in the 1813 War of Liberation. Emperor Napoleon would soon be overwhelmed and forcibly removed from power by 1814, as Sixth Coalition forces poured into France’s capital. Austria would become significant in the restructuring of power in Europe post Napoleon while assisting the Seventh Coalition in defeating the remaining French loyalist forces in 1815.

Revolutions of 1848 (Jan 12, 1848 - 1849)

Austro-Prussian War (14 June – 22 July 1866)

Fought between Austro-Hungarian forces and Prussia, one of the Habsburgs’ longest standing rivals, Francis Joseph I (r. 1848-1916) , Emperor of Austria and King of Bohemia and other territories, saw himself suffering a major blow to Austria’s power over Hungary and other nations to Prussia, which continued to expand its hegemony over Europe. Prussia was under the leadership of King William I and prime minister turned Prince Otto von Bismarck-Schönhausen, with the latter assuming office in 1862 and holding Napoleonic ambitions to wrestle control away from the German Diet, which had long held influence over Central Europe. This would come with a declaration of war against Francis Joseph I, as Bismarck would begin his attack with a historical first Blitzkrieg on June 16, 1866. The Austrian forces were quickly overrun and soon launched a desperate defense led by Commander Benedek in July at what would become the Battle of Königgrätz in Bohemia, the largest battle during the war. It led to significant losses on both sides with the Prussians claiming victory and Francis Joseph signing the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, a treaty that separated Hungary and Austria as two administrative states: Austria-Hungary.

III. World War I and the Czechoslovak Legion

Causes of Czech opposition to Austro-Hungarian rule

Sources:

Benes, Jakub S. “THE GREEN CADRES AND THE COLLAPSE OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY IN 1918.” Past & Present, vol. 236, no. 236, gtx028, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtx028, 1-31.

Crankshaw, Edward. The Habsburgs: Portrait of a Dynasty. 1971. The Viking Press, 1 Jan. 1972, 228-257.

Lein, Richard. “The Military Conduct of the Austro-Hungarian Czechs in the First World War.” The Historian (Kingston), vol. 76, no. 3, 2014, pp. 518–49, https://doi.org/10.1111/hisn.12046.

Monroe, W. S. Bohemia and the Čechs : The History, People, Institutions, and the Geography of the Kingdom, Together with Accounts of Moravia and Silesia / by Will S. Monroe. G. Bell, 1918, pp.50-156.

Pánek, Jaroslav, and Oldřich Tůma. A History of the Czech Lands, Karolinum Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uh/detail.action?docID=5720123.

Rauchensteiner, Manfried. The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918. Translated by Alex J. Kay et al., 1st ed., Böhlau, 2014.

Slačálek, Ondřej. “The Paradoxical Czech Memory of the Habsburg Monarchy: Satisfied Helots or Crippled Citizens?” Slavic Review 78.4 (2019): 912–920.

Vardy, Nicholas A., Barany, George, Várdy, Steven Béla, Macartney, Carlile Aylmer. "history of Hungary". Encyclopedia Britannica, 18 Mar. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Hungary. Accessed 6 November 2025.

“Czechs and Slovaks Fighting for Independence during World War One.” Europena, Europeana Foundation, 19 July 2018, www.europeana.eu/en/stories/czechs-and-slovaks-fighting-for-independence-during-world-war-one.

“The Foundation of Military Intelligence in Czechoslovakia and Its Beginnings.” Vojenské Zpravodajství, vzcr.gov.cz/en/historie. Accessed 6 Nov. 2025.

Images:

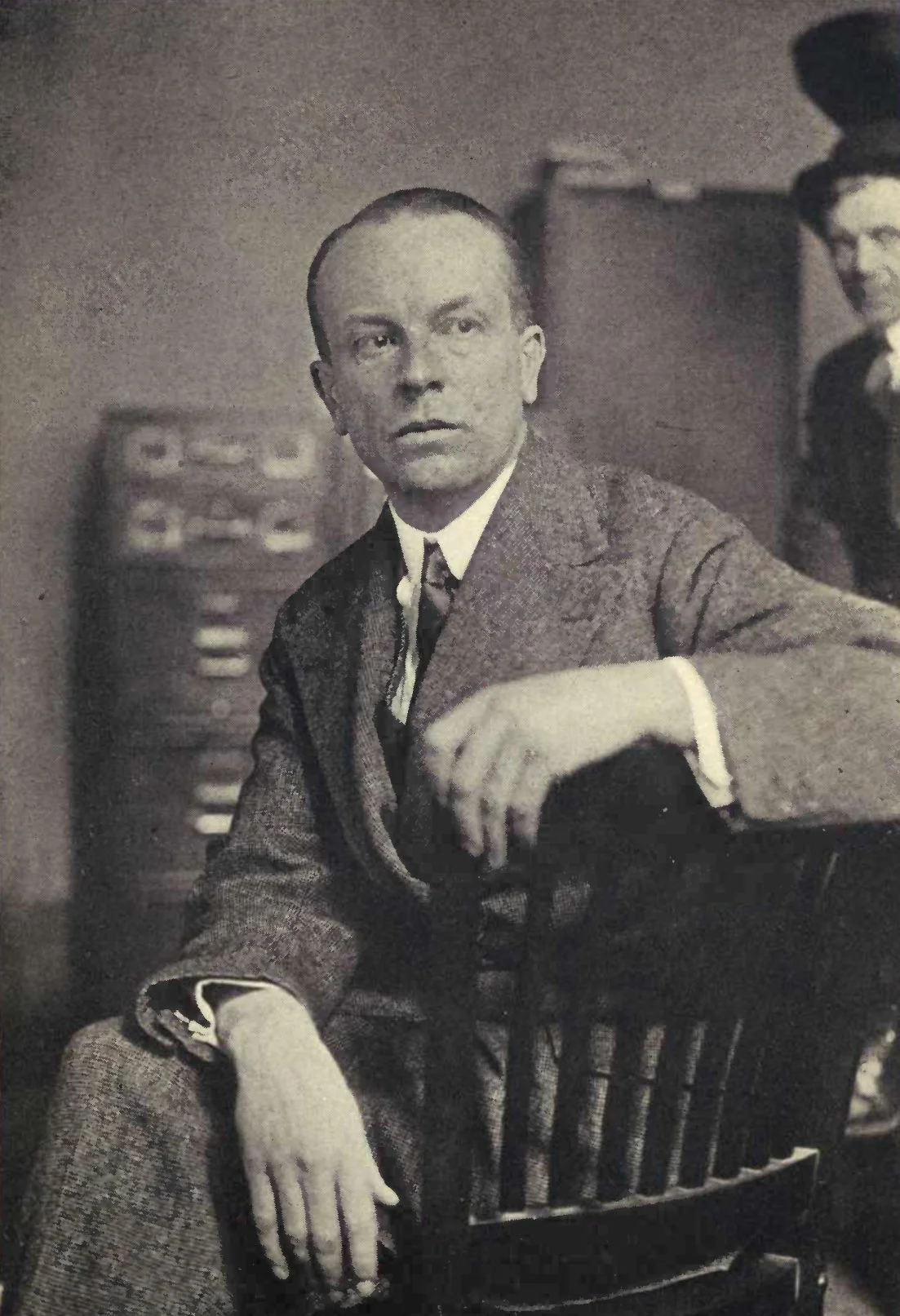

Discontent had been brewing among recruited Czech and Slovak soldiers and reserve officers within the many ethnic minorities that formed the military of Austria-Hungary well before the Great War. They would be drafted into the army of the Habsburg monarchy, known then as the Imperial and Royal Army or the Austro-Hungarian Army. Bohemian citizens had become wary of their increasing loss of autonomy, especially in the 19th century under Prince Metternich. Mettenich practically ruled with an iron fist in place of Emperor Francis II and later Ferdinand IV (1835-48). While seen as a reign of governance that was stable and relatively prosperous, more and more saw the Habsburg monarchy as a repressive entity that enforced Germanic supremacy over Czech and Slovak identities and cultures, and while they would not openly challenge initially, movements for the reformation of Bohemia in Austria-Hungary as a federalized republic began to emerge during the reign of Habsburg’s last monarch, King of Austria and Bohemia, King of Hungary Franz Joseph I (r. 1848-1916).

Emperor Franz Joseph I was effectively a scapegoat for the sharp decline of the Habsburgs’ control over their empire. This was over decades after the loss of several northern German territories to the Kingdom of Prussia after the Austro-Prussian War. Austria’s hegemony was crippled, with Austria-Hungary being separated into 2 separate administrative states under the monarch, being labeled as the Dual-Monarchy. Emperor Franz Joseph I would attempt to consolidate control over his remaining subjects through neo-absolutism in the mid-1800s. He ruled as an absolute monarch and was known for his authoritative style of governance despite pushing for administrative reforms in education and government. This accelerated the centralization of administrative control of Bohemia and all other states under Austria.

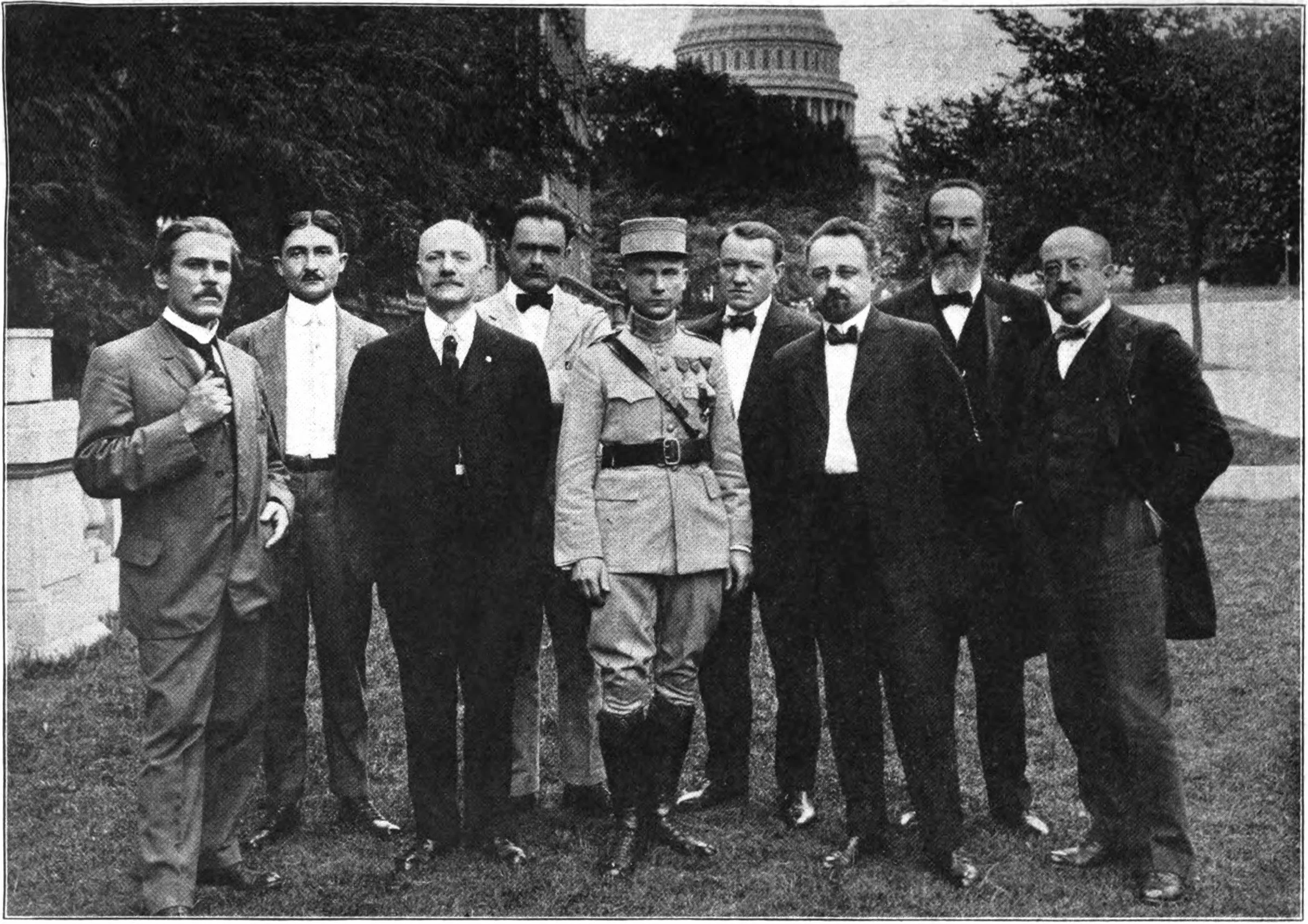

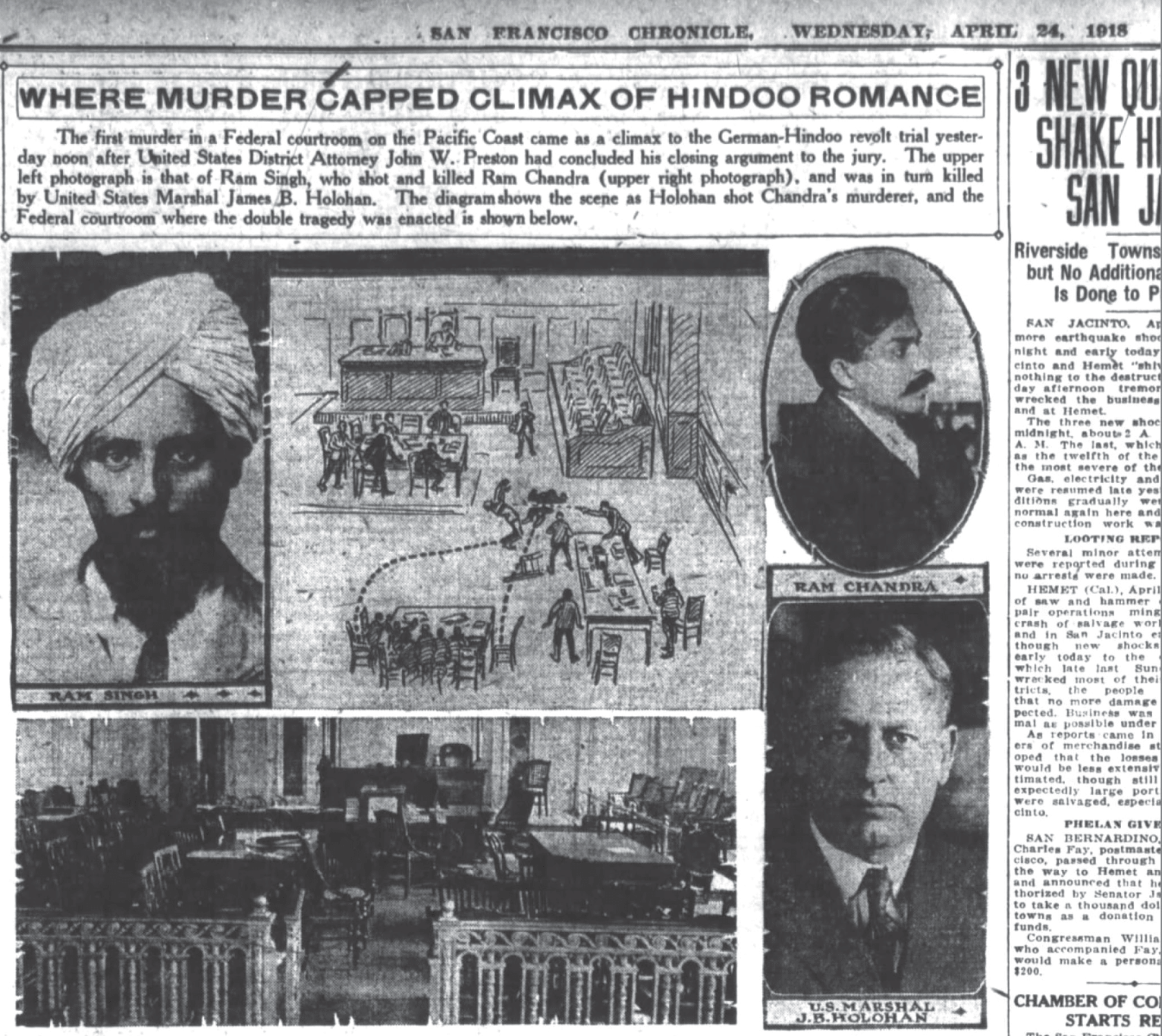

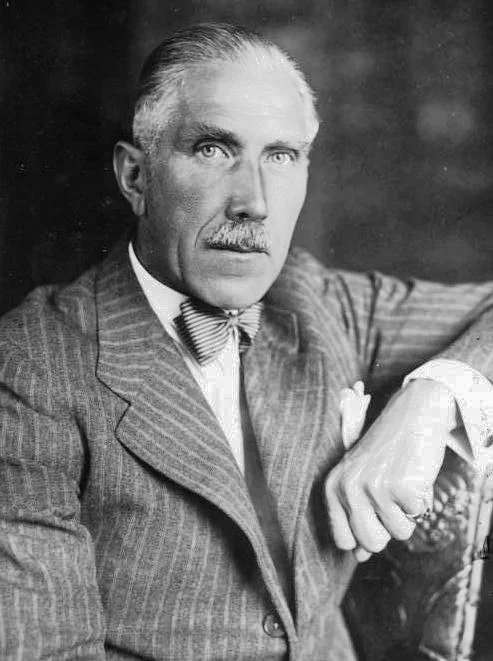

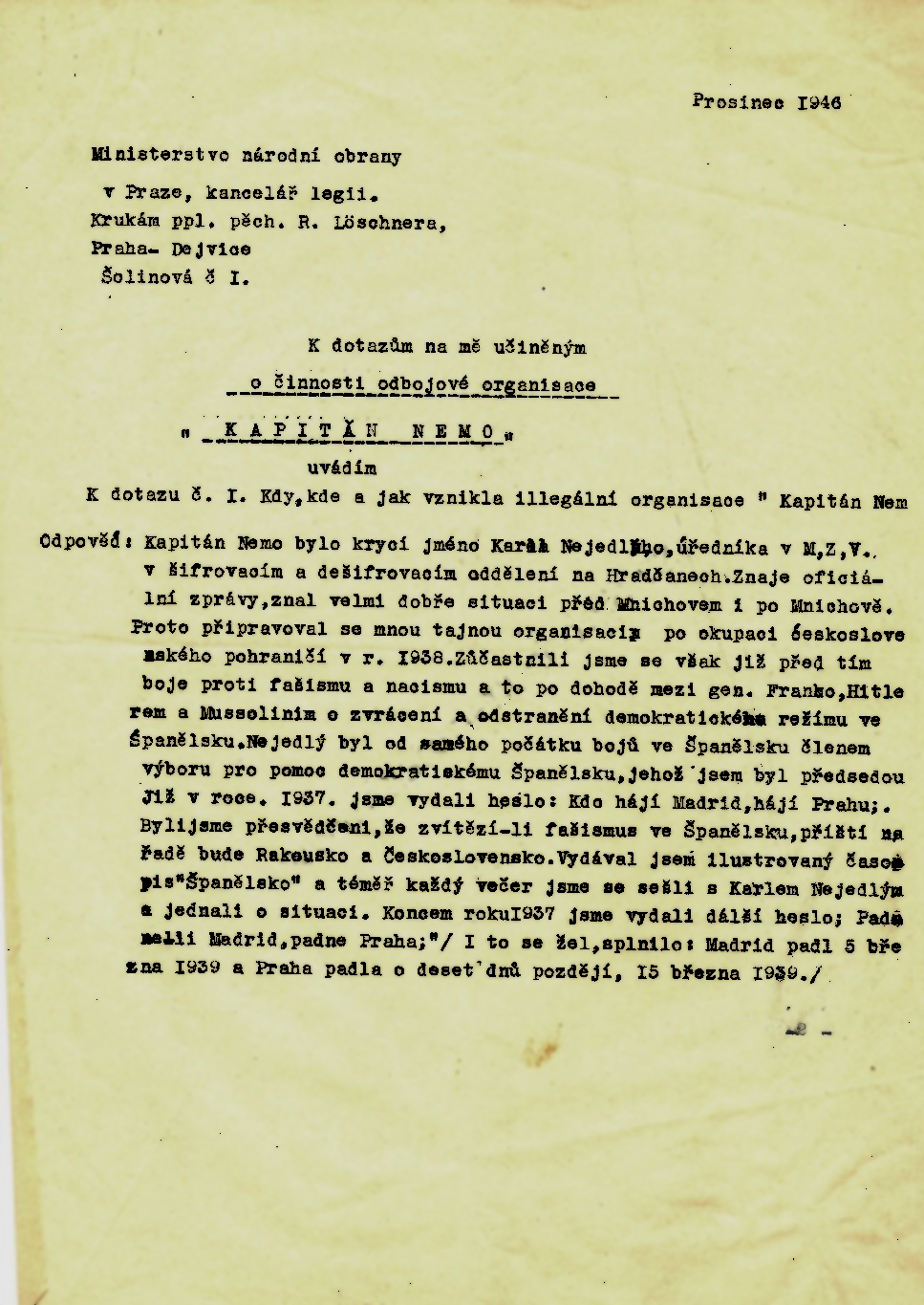

Resentments grew amongst subjects of the Habsburg crown over the loss of land rights and increasing encroachment of the monarchy in administrative governance. White nationalism had been brewing within the Empire as far as the 1848 Revolutions in the Austrian Empire and even beforehand, nationalist sentiments grew amongst the Czechs, Hungarians, and other ethnic groups. With the establishment of the Dual Monarchy, Czech citizens demanded compensation and political reformation, with the empire as a multiethnic structure becoming strained. Furthermore, many nations, including the entirety of Europe, found themselves strung along by war treaties that compelled them to aid their allies, creating a political powder keg. This would ignite on June 28, 1914 with the infamous assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Francis Ferdinand I, in Sarajevo. The brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I, he was shot alongside his wife by a Bosnian-Serb nationalist in the capital city of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This shocking event led Austria-Hungary to declare war on Serbia a month later. This declaration triggered longstanding treaties and military alliances across Europe that would draw much of the world into several years of war on an unprecedented scale.