Working Underground Against the Nazi Regime: The Story of the Cebe-Habersky Family

Here at the Czech Center Museum Houston, we have several examples of traditional kroj from across the area of what is now the Czech Republic and Slovakia. However there is one, a small child’s kroj, which along with its amazing handsewn detail, is notable because it belonged to the Cebe-Habersky family. The Cebe-Haberskys lived in Prague during World War II and were part of the Nazi resistance of the time. Their story is one of resilience and hope during a time of unrest and uncertainty.

Family history and background

Jaroslav Cebe married Otilie Kuchar on June 6th, 1931. Jaroslav was a lawyer by trade, born in Habry to a father who was a doctor and a mother who loved botany and art. He grew up with some political connections to those in the Czechoslovakian government, particularly through his sister Mila, who married Jaromír Šámal, the son of Chancellor Přemysl Šámal. Chancellor Šámal served as the mayor of Prague as well as the Head of the Office of the President of the Republic under both President Benes and President Masaryk (Hajšman 1946).

Otilie also came from a well connected family background; her grandfather was Dr. Josef Herold, a famous Czech politician, and she spent the early years of her childhood in Kamarov where her father worked in a steel factory. After their marriage, Jaroslav and Otilie moved into an apartment in Prague, at No. 5 Francouzaka, with Otilie’s parents living on the floor below them.

They welcomed three children into their family: Dagmar, the oldest daughter was born April 1932, Jack, middle son, was born May 1934, and their youngest daughter Ajka was born May 1939 during the beginning of the Nazi occupation of what had once been Czechoslovakia.

The Cebe-Habersky Family circa 1940s. From left to right: Ajka, Otilie, Jack, Jaroslav, and Dagmar Cebe-Habersky. Photo taken from The South Carolina Review, Fall 2013.

Events leading up to resistance work

The Nazi government took control of Czechoslovakia as part of the Munich Agreement following World War I. With few supporters, Czechoslovakia was left to either accept German rule, or to fight against the Germans themselves (Mastny 1971).

On March 15th, 1939, Czech citizens were warned against resisting the Nazi army as they marched into Prague unhindered. Many Czech government officials left their offices, with some government leaders and military intelligence fleeing abroad to other countries and eventually to London, England. This set the stage for many concerned Czech citizens, including Jaroslav Cebe-Haberksy, to aid in resistance against Nazi officials in whatever way they could.

1939

“It was natural for me to start underground activities…This was a unique generation, forgotten by Western Europe, but proud, courageous, and heroic” -Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky

Jaroslav joined what came to be known as the Šámal group, a band of resistance lead by his sister’s father-in-law Chancellor Přemysl Šámal. Šámal had experience running resistance groups as he was instrumental in helping with the resistance that lead to Czechoslovakia’s independence. In a memoir of Šámal’s life, Jaroslav is mentioned as being his deputy and devoted to Šámal and the efforts he made as part of the resistance (Hajšman 1946). Although the full extent of Jaroslav’s work as part of the Czech underground resistance is unknown, his own recollections tell us a few things about his efforts (Cebe-Habersky, 1946):

Jaroslav mentioned aiding Czechoslovak leaders and official in fleeing the country, many of whom helped with President Benes’ exiled government in London or joined Allied military forces.

He helped with organizing meetings between different resistance groups and passed communications between in country groups and those outside of the country.

Jaroslav also talked about helping to fund and publish anti-Nazi leaflets and other underground publications that were then distributed in Prague and throughout the rest of the country. Even before the war began, over 20 different underground publications were being shared around the country (Bryant 2007:39).

His work as a lawyer allowed him to use legal affairs as a camouflage to host resistance meetings.

Jaroslav went by the cover name “Habersky” for his protection during his time as part of the underground, a name chosen because he was born in Habry. His cover was so well maintained throughout the war that many thought that Habersky had died during the war, not realizing that Jaroslav and Habersky were the same person. After the war, Jaroslav officially added Habersky to the family’s last name.

Around Christmas time in 1939, information about underground resistance groups reached the Gestapo. At the time, there were three large Czech resistance groups: Nation’s Defense (made up of military personnel), Political Center (former president’s close associates and likely the resistance group the Šámal group was most closely associated with), and Committee of the Petition “We Remain Faithful” (comprised of left wing unionists). The Nation’s Defense resistance group was raided by the Gestapo in December of 1939, leading to the arrests of key military officials and causing the remaining members of underground resistance groups to consolidate into one group (Bryant 2007).

Most likely as a result of the raid against the Nation’s Defense group, the Gestapo received the names of those associated with Přemysl Šámal, including Jaroslav. He and others went into hiding at various apartments around Prague, continuing meetings and work with the resistance as much as they were able to. At the time, the Czech borders were open and many of their contacts escaped across the boarder with the help of Jaroslav, including General Karel Janoušek, who helped organize the Czechoslovak air force within the British Royal Air Force, becoming the only Czech Air Marshal for the RAF (Valdová, 2012). Jaroslav often considered leaving the country as well, but worried about the safety of his family; in the end, many of his fellow resistance fighters who left the country came home to find that their families had been killed by the Nazis in retaliation for their escape.

“The Christmas spirit had left me, as it had many people who had weary faces hardly showing in the dim light, each with his own worry about what the future would bring.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Trying to escape the depression that seemed to hang over Prague, and to try to forget the fact that Jaroslav was unable to join them, Otilie took the children by train to visit family living in Čerčany for Christmas. Once they arrived at the house, late at night, a strange man knocked on the door. He spoke fluent Czech and claimed to have important messages that needed to be passed on to Otilie’s husband. Otilie recalled she was convinced of the man’s sincerity until he began to insist she tell him where Jaroslav was hiding. This convinced Otilie that the man was a Nazi spy; she lied in her response to him, saying Jaroslav was on a skiing trip in Sumava. The man left and Otilie reached out to contacts in Prague the next day to warn Jaroslav about the man.

Unbeknownst to Otilie at the time, the same strange man had visited Jaroslav in his office right before he went into hiding. Jaroslav was also convinced that it was part of a Nazi trap and refused to disclose any information about the resistance to the man; he chose not to tell Otilie about the incident in order to give her deniability. In fact, Jaroslav kept Otilie out of underground operations as much as he could for the same reason. After Otilie’s encounter with the man, the same man appeared and chased Jaroslav as he was traveling to an underground meeting. Jaroslav was able to flee out of a side entrance in a café and escape, but it left no doubt that the Nazis and Gestapo were interested in Jaroslav and his activities with the resistance.

1940

After being apart for so long, Otilie and Jaroslav worked to arrange a way for Jaroslav to safely come see the children. Dagmar and Jack were staying in Mnisek with Jaroslav’s parents, while Otilie had baby Ajka with her in Prague. They agreed that once it was safe for Jaroslav to return home so they could take the bus to Mnisek, Otilie would place a wooden statue of St. Mikuláš (St. Nicholas) in the window of their apartment to indicate that the coast was clear. They were both unaware that the Gestapo were occupying the apartment across the street and monitoring all movement in and out of the Cebe-Habersky home. On the morning of January 6th, Otilie placed the statue of St. Mikuláš in the window of No. 5 Francouzska, and Jaroslav came to meet her at the home after being sure he was not followed.

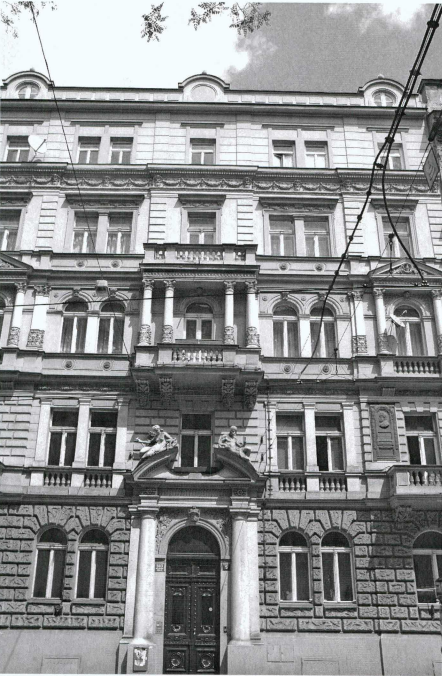

No. 5 Frankcouzska, Otilie’s family home where she and Jaroslav moved into one of the apartments after they were married. The statue of St. Mikuláš was most likely places in one of the windows in the upper floors as that is where Otilie and Jaroslav lived with their family. Photo taken from The South Carolina Review, Fall 2013.

While waiting for the bus to depart for Mnisek, they stopped for a cup of coffee. As they left the coffee house, the same strange man who had confronted Otilie and Jaroslav before appeared yelling “Geheime Staatspolizei! Sie sind verhafted!” (Secret State Police! You are under arrest!). The man arrested Jaroslav, putting him in the car with two other Gestapo officers and driving away, leaving Otilie with baby Ajka in the street.

“It happened so fast and in such a short time that I believed it had been a bad dream. I do not remember how long I stood there, waiting for something to happen, for Jaroslav to come back.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Otilie returned home where she called a family friend to tell him about Jaroslav’s arrest and not to come to the house. Not long after she returned, three men arrived with drawn revolvers to arrest Otilie as well. Otilie left baby Ajka in the care of the maid and was taken to the former Petschek Bank Palace, which was now home to the Gestapo headquarters in Prague.

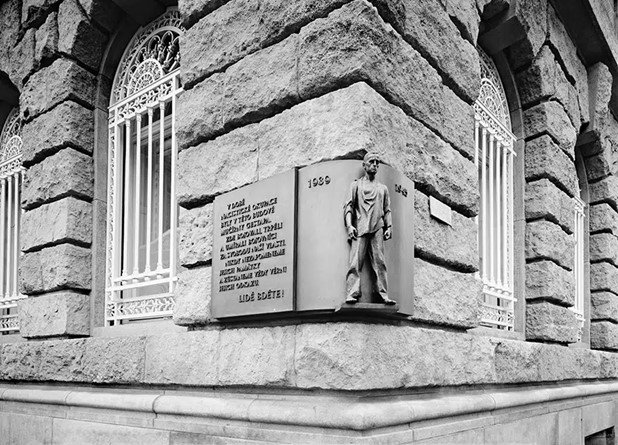

The Petschek Palace was built by Jewish banker Julius Petschek in the 1920s and was sold in 1930 when the family emigrated to Britain before the building came under Nazi control during the occupation. Thousands of people including Prime Minister Alois Elias and World War I hero Josef Masin were held and subjected to torture by Nazi guards in the bank vaults before either being executed or sent to concentration camps (Pohanka 2023).

Memorial plaque for the victims of torture on the corner of Petschek Palace. Photo by David Kumermann. Taken from https://praha.mkc.cz/en/place/kolaborace/petschkuv-palac.

“At the Gestapo headquarters we entered a small room with the radio playing full blast to cover the sounds coming from adjoining rooms where people were interrogated and tortured. They asked me about Jaroslav’s underground work and people visiting the apartment. Happily, I knew nothing and somehow made them believe it.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

While Otilie was being interrogated, Jaroslav was in a neighboring room, made to believe Gestapo officers were torturing Otilie in order to persuade him to talk. Although Jaroslav knew that this was likely not actually happening, he said this was the hardest moment out of all the other forms of torture he would be put through over the next few years as a Nazi prisoner. Otilie was able to convince the Gestapo that she did not know anything about the resistance and she was allowed to return home under Gestapo guard and put on house arrest. Jaroslav’s mother returned with Dagmar and Jack and word spread quickly throughout Prague and the underground that Jaroslav and the rest of the Šámal group had been arrested. Otilie’s father and mother moved in with her to help with the children and Jaroslav’s law office continued to be run by a friend and clients continued to support his office so that his family would be taken care of while he was imprisoned.

Jaroslav and the rest of the Šámal group were eventually moved from Petschek Palace to Pankrac Prison in Prague. Otilie tried several times to visit Jaroslav while he was kept there. Often she would wait for hours, hearing screams of pain as prisoners endured beatings only to be told to return later if she wanted to see her husband. Come Sunday, Otilie would take the children every week to walk by the prison in order to feel close to Jaroslav.

Pankrac Prison was built in 1889 and quickly was commandeered as a political prison for the Nazi Gestapo. The prison quickly became overcrowded with horrible conditions for those imprisoned there. Three cells held the prisoners who had been condemned to death and a guillotine was constructed to carry out these death sentences. About 1,087 prisoners were executed there over the course of the Nazi occupation and several Nazi war criminals were also executed on the site after World War II as well (Miller). Eventually, the prison would once again hold and execute political prisoners under the Czech communist regime.

"Each day had its dramatic impact in many families: terror got worse, and the food scarce. Both our parents helped me with money and food but, most of all, with their love”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

By April of 1940, over 1,500 suspected resistance members had been arrested and thrown in jail to await trials (Bryant 2007). Former President Benes began working to establish communications between resistance groups in occupied Czechoslovakia and London, pushing for the training of parachuters who could be sent into occupied Czech lands to establish means of reliable communication between those in country and London. At the same time, President Benes pushed for recognition of his Czech exile government in London and one of the only countries to recognize this government was the Soviet Union. This caused President Benes to establish close ties and an alliance with the USSR, which would impact the history of Czechoslovakia even after the end of the war.

For Czechs still in country, particularly in larger cities like Prague, by the time of winter 1940, food was extremally scarce and restricted. Most are unable to find fresh fruits and vegetables and rice was only available to the sick or pregnant women. Black markets for food goods boomed in these areas (Bryant 2007).

1941

In September of 1941, after reports of unrest in Czech lands, Reinhard Heydrich was appointed Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. Heydrich was one of the main architects of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” and saw his post in Bohemia as an opportunity to complete three objectives in order to crush Czech resistance: 1. to mobilize the area to aid in the German war effort, 2. root out and crush any Czech resistance, and 3. to impose martial law and enact tribunals. During his time in Pankrac Prison, Jaroslav mentioned overhearing discussions among Gestapo leaders, including Reinhard Heydrich and SS officer Karl Hermann Frank planning to target higher Czech officials, including Prime Minister General Alois Elias, who was the head of Czech government under Nazi rule but maintained contact with exiled government officials (Cebe-Habersky 1946). Jaroslav smuggled out warnings from prison to General Elias that he should attempt to flee the country, although he was not successful as General Elias was arrested just before Heydrich’s appointed to Reich Protector and was eventually killed in June of 1942 (Mastny 1971). By October 1941, President Benes was working on plans for an assassination of Reinhard Heydrich from London.

Jaroslav and the rest of the Šámal resistance group were moved to a new prison in Moabit-Berlin while they awaited trial. While waiting for their case to be heard, prisoners at Moabit spent their time sewing buttons on uniforms and crafting military leather helmets. They were kept in single cells under close supervision and could only see each other when walking in the yard once a day, but were unable to talk (Cebe-Habersky 1946). Allied forces’ threats against Germany led to Nazis taking a hard stance against those rebelling in occupied countries with increased arrests as well as death sentences. Law suits against the different resistance groups slowly come in, with Jaroslav and others mentioned as part of the “Šámal mafia”. Premsyl Šámal himself did not make it to trial as his health was severely impacted by his prison stay and he died in Spring 1941 (Hajšman 1946).

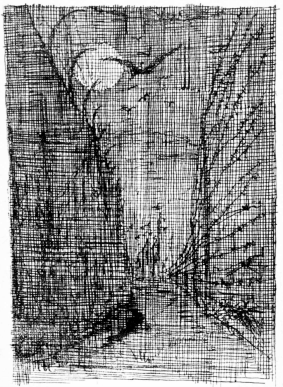

Print by J. Šváb included behind the title page of Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky’s book Dům mrtvých. Věznice Moabit a Plötzensee 1940-1942 (House of the Dead. Moabit and Plötzensee Prisons 1940-1942). The book details Cebe-Habersky’s experience while awaiting his death sentence in Germany.

Otilie was able to visit Jaroslav a few times during his stay at Moabit. They both use this opportunity to receive and send out reports about both the conditions in the prison as well as to receive news of what was happening in Prague, exchanging small scraps of paper with information written down while Jaroslav’s mother distracted the guards during their visit (Cebe-Habersky 1946).

On December 7th, 1941, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into World War II.

December 8th, 1941, Jaroslav and the others in the Šámal group were put on trial. Jaroslav noted that the investigating judge for their case was also the sentencing judge, a move that was highly illegal (Cebe-Habersky 1946). The entire Nazi military school housed nearby came to see their trial. Even though the Gestapo had uncovered very little about the group’s extensive underground activities, the sentence had already been decided and the trial was just a formality; all defensive witnesses were dismissed as irrelevant to the case and their lawyers had very little opportunity to speak for the men they were suppose to be defending. At the end of the trial, Jaroslav and his associates were all given death sentences and moved to Plötzensee death prison to await their fate.

Plötzensee was originally build during the 1860s and beginning in 1933, it was used for interrogations and executions of prisoners as well as a location for political trials. Between 1933 and 1945, 2,891 people were sentenced to death and executed at the prison by guillotine or hanging. Plötzensee was a huge complex, with several “houses of death” for those who awaited execution. Prisoners were given ill fitting clothing, beaten by guards and continuously reminded of their eventual fates. Windows in the cells did not close all the way and prisoners were subjected to extreme weather conditions as they awaited their deaths. While new was often able to be smuggled in to other prisons, at Plötzensee, prisoners resorted to reading old newspapers used in the toilets or communicating with new prisoners for any news outside the wall of the prison (Cebe-Habersky 1946).

As the Šámal group was being moved to Plötzensee, President Benes assassination plan was being put into action. Known as Operation Anthropod, Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš were trained by British intelligence and military to parachute into occupied Czechoslovakia in order to carry out the assassination of Reinhard Heydrick. When they parachute into the country, Gabčík was injured in the landing and errors in their landing zone left them cut off from their contacts. By chance they were found by a man with connections to the underground resistance in Prague, who got them set up with appropriate papers in a safe house (MacDonald 1998:120).

1942

Following her husband’s trial and ultimate death sentence, Otilie and the children continued to live in their apartment in Prague. Conditions in the city continued to worsen, with food becoming more and more scarce, leaving Otilie (and many other Prague residents) to travel to the countryside to smuggle food back to Prague. Unable to help the resistance in other ways, Otilie began renting out part of the floor and apartment to Jewish families no one else would help.

“This again was against Nazi regulations, but it was our way to help.” -Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Twice Otilie was able to receive a 24 hour travel visa to be able to go see Jaroslav in Plötzensee. Both times she traveled all day for the chance to be able to visit with her husband for ten minuets before traveling through the night back to Prague before her visa expired. Jaroslav’s mother traveled with her, once again distracting the guards so that Jaroslav was able to pass reports about the prison to Otilie and she was able to give him reports of what was happening in Prague.

Execution site at the Plötzensee prison. At Plötzensee, the Nazis executed hundreds of Germans for opposition to Hitler, including many of the participants in the July 20, 1944, plot to kill Hitler. Berlin, Germany, postwar. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/execution-site-at-the-ploetzensee-prison.

By February, Plötzensee has become so overcrowded that Jaroslav and his fellow prisoners were forced to stay two or more to a cell, something that made imprisonment much more bearable. Disease was common within the prison and Nazi guards often poisoned the food prisoners were given; the prisoners themselves pass the time talking, communicating with each other through the walls, and reading books they were allowed to borrow from the prison library. Jaroslav mentioned their communications with fellow prisoners and the outside world being aided with the help of a kind priest, Father Luhow, who helped pass notes, bringing news of what was happening in the war and back home in Prague. Father Luhow also reported which prisoners had been executed and at times was able to forewarn prisoners of their impending executions so they would have time to write their last letters to family members (Cebe-Habersky 1946).

On March 1st, for the first time since they parachuted in to the area, Gabčík and Kubiš are able to get in touch with London and confirmed that they are planning to move forward with the assassination attempt on Reinhard Heydrich. When the underground resistance learned of this plan, they were appalled and asked for Operation Anthropod to be canceled, fearing the fall out and retribution from the Nazi regime if the attempt was successful. President Benes does not cancel the order, but also does not confirm it and Gabčík and Kubiš continue to move forward with preparations (MacDonald 1998:144).

April 12th, tragedy strikes the family as Karel Kuchar, Otilie’s father dies of a heart attack at age 53. Otilie’s mother was left in shock and unable to function for months, leaving Otilie to take care of her and the children without any help. Otilie refused to tell Jaroslav what happened during her next visit as she wanted to keep him strong as he awaited death with dignity.

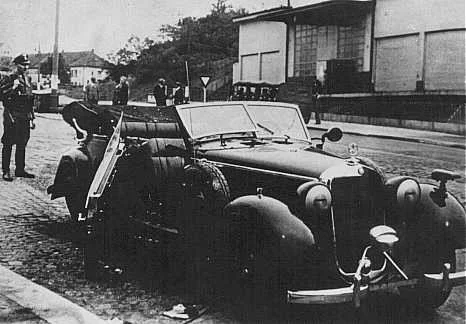

On May 27th, the assassination attempt is carried out. When Heydrich’s car rounds a corner, Gabčík jumped out, pulling his gun, which then jammed. Heydrich stood up, pulling his pistol, giving Kubiš time to attempt to throw a bomb into the car. The bomb missed, exploding the rear wheel of the car, sending up shrapnel that hit Heydrich, who suffered broken ribs, a ruptured diaphragm and shrapnel in his spleen. Although not killed outright, Heydrich eventually succumbed to his wounds and died June 4th, 1942. The assassins were eventually sold out by another Czech resistance operative and killed (MacDonald 1998).

The damaged car of SS General Reinhard Heydrich after an attack by Czech agents working for the British. Prague, Czechoslovakia, May 27, 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/attempt-to-assassinate-ss-general-reinhard-heydrich.

In retaliation for Heydrich’s death, Nazi officials under the guidance of SS Officer Karl Frank razed and destroyed the village of Lidice. It is unknown why Nazi officials selected Lidice, a small Czech village 12 miles outside of Prague, as there was no connections between the village or the assassins. The men of Lidice were rounded up and shot; the women and children were deported to concentration camps and the town was burned to the ground. Of the 89 children that were gathered from Lidice, 9 of the children were selected and sent to a group home to be adopted and raised as German citizens (MacDonald 1998).

An SS officer surveys the ruins of Lidice during the destruction of the village. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Library of Congress. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa5391

Along with the razing of Lidice, many other Czech citizens were rounded up and shot or deported to concentration camps. Among them was Jaromír Šámal, Jaroslav’s brother-in-law and Chancellor Přemysl Šámal’s son, who was shot and killed, despite not having any connection to the resistance.

“…now it was he who left us and died, although there was not the slightest thing which the Gestapo could produce against him. His only crime was that he was Chancellor Šámal’s son.” -Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Mila, Jaroslav’s sister and Jaromír Šámal’s wife, went to Gestapo headquarters to inquire about what had happened to her husband after he disappeared from their apartment. She was arrested and sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, and eventually to Auschwitz. Mila and Jaromír’s two children, Jiri and Alena were kidnapped by the Gestapo after her arrest and the family was unable to find out where the children had been taken.

Stolpersteine for Jaromír and Mila Šámal. Stolpersteine (stumbling blocks) are memorial plaques places in sidewalks to commemorate victims of Nazi persecution across Europe. They are placed at the person’s home or workplace, and have the name of the victim, their birthdate, arrest date, and fate. https://stolpersteinecz.cz/en/rejstrik/.

Within Plötzensee, Jaroslav watched as many of the Czech prisoners were executed, with entire resistance groups and some as young as 12 being taking to meet their end (Cebe-Habersky 1946). In August, Jaroslav was summoned to act as a witness in the trials of two other Czech resistance groups, delaying his own execution. He recalled testifying adamantly of the innocence of one Mrs. Pittaismanova, who mediated connections with Polish resistance, ran several women’s resistance organizations, and helped British intelligence. Jaroslav’s insistence of her innocence branded him an untrustworthy witness and he was forcibly removed from the court room and barred from testifying at other trials he originally was asked to be a witness for.

September brought continued threats of impending death for Jaroslav and those who were a part of his resistance group. With more Czech prisoners coming into Plötzensee, Jaroslav learned of the death of his brother-in-law after the Heydrich assassination and worried about his sister Mila and her children, although he was not told by family of their unknown fates. He wrote of finding solace in the books they were able to read and in discussing moral and ethical questions with fellow inmates (Cebe-Habersky 1946). Letters were contently being written to family as the prisoners await their deaths, hopeful that their last words would make it those they love. Jaroslav, in his book Dum Mrtvych: veznice Moabit a Ploetzensee, 1940-1942, writes of the bravery and unfailing honor in which his fellow prisoners walked to their deaths.

Winter brings a sudden change as Jaroslav and the remaining members of his resistance group are informed that their death sentences have been overturned and changed to 15 years hard labor. He was never informed to what cause this change in his sentence and although this gave hope to other prisoners in Plötzensee, executions continued at an alarming rate with no others given changes to their sentencing. Jaroslav was then transferred to Kaisheim prison and later to Amberg prison to serve his labor sentence and although Otilie attempted to visit him before he was transferred, she was unable to receive permission.

Both Kaisheim and Amberg prisons housed both criminal and political prisoners during the Nazi regime. Prisoners were put to work at local munitions factories, shoe factories or other forms of forced labor. Many of the prisoners were also taken to concentration camps like Dachau or Mauthausen to work or as part of their sentencing during the course of the war.

1943- 1944

While Jaroslav continued to serve his prison sentence in Kaisheim and Amberg, life for Otilie and the children continued in Prague. Many of the inhabitants of Prague continued to face extreme food shortages, often traveling to the countryside to find food to smuggle back to Prague. While public schools are still running, they quickly became centers of Germanization, striving to raise the next generation within Prague to be upstanding German citizens (Bryant 2007:196). Parents begin fearing that their children will report and turn them in for any anti-Nazi behavior, leading any of the remaining resistance movements to go completely underground and cease many of their activities.

1945

Bombing of Prague by U.S. Air Force in 1945. Photo from Archive of DPP. https://english.radio.cz/80-years-ago-american-bombs-fell-prague-8842882.

By spring 1945, the Germans were in full retreat and the invasion of France by allied forces had been successful. Allied forces began pressing into occupied Czechoslovakia, leading to a mistaken air force bombing on residential areas in Prague. Otilie and the children survived the bombing, although their neighbor’s home was hit directly, destroying the home and killing their neighbors. Otilie decided that it is too dangerous for them to remain in Prague and they immediately pack up to stay with Jaroslav’s parents in Mnisek. Due to Nazi forces, the train from Prague was unable to reach Mnisek, forcing the family to walk the last 4 miles through the forest to reach safety.

“We tried to keep the kids going as we took the long walk across the deep forest. Some good people gave us a kerosene lantern which helped a little to find the small path through the woods. I knew where it was, but in our excitement and tension it was hard to follow it at night. We kept telling stories to the children who were afraid of the howling owls. The path seemed endless.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Jaroslav’s sister Mila was able to send a few letters from the concentration camp to her parents in Mnisek. Jaroslav’s parents worried about how Mila would react to finding that her children were taken, so they continued to tell her that the children were staying with them in order to keep her from losing hope. Otilie had her children write letters to Mila pretending to be their cousins. Throughout her time in the concentration camp, Mila never suspected anything was wrong with her children and said that believing her children were safe carried her through the hardest days.

Otilie eventually moved with the children to Čerčany so that the children would be able to continue to attend school in Benešov. She fondly remembered working to grow a garden there and how they had more food at this point than at any other time during the war. The children had to walk 2 hours to Benešov to attend school, which they gladly did until Otilie deemed it too dangerous with SS headquarters close to Benešov and reports of German troops razing villages as they retreated to Germany.

Benešov was the designated military training area for the Nazi military forces beginning in October 1941, forcing out many of the local Czech population in the surrounding villages. It housed the Relocation Office for German occupied territory. In March 1943, Germans moved their headquarters from a sanitarium to the Konospiste Castle, using forced labor from both Czech residents and labor camp prisoners to build extensive military training grounds. Benešov also became home to a camp for those of mixed-Jewish ancestry, and although not formally labled a death camp, the conditions were terrible (Meziřekami.cz).

May brings fighting to the streets of Prague. The underground called on the remaining citizens to begin fighting the Germans to push them out of Prague, counting on aid from American troops stationed in Rokycany, unaware that an agreement had been made that the Russians were to liberate Prague. Karl Hermann Frank, who had helped orchestrate the destruction of Lidice, ordered violent retaliation against any form of Czech resistance. On May 5, Czech police overtook the local radio station, encouraging those still in Prague to rise up against the Nazis. Resistance fighters took over Gestapo headquarters, removed German signs, attacked and disarmed soldiers and worked to set up barricades and cut off access to utilities. May 6, German reinforcements arrived in Prague followed by German bombers that overwhelm Czech resistance. On the 8th a cease fire was negotiated between the resistance group and the Nazis and Prague was finally liberated by the Red Army on May 9th after devastating Czech losses (Naillon).

Civilian and resistance fighters in the streets of Prague. Photo from Czech Radio. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/prague-uprising-1945.

With the arrival of the Red Army, Otilie was afraid to stay alone with her children in Čerčany, so they decided to go stay in the village with a former maid.

“Just as we were in the underpass, an SS tank roared towards us with its gun aiming straight at us. We stopped to gasp and jumped to the edge of the road. I held Ajka tight against my heart. The tank did not shoot and did not run over us. It disappeared on the road, the last fury of war”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

As the Russian army arrived in the countryside, many Czechs found themselves under threat from the Red army. Soldiers forced their way into homes, stealing food and often raping and beating those they found there. Otilie decided it was no longer safe to stay in the countryside and chose to return home to Prague. She hoped that if Jaroslav had survived his time in Amberg, he would first try to find them at their home in Prague. Although the war was over, Otilie noticed that there was little to be celebrated in Prague.

“There were no celebrations, no festivities or parades. Faces were weary, sad and pale. Wounds were still fresh, the losses were enormous. Long years of war did a thorough job. Too many did not return: fathers, mothers, children, whole families. Hearts were empty, hands were tired.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

After days of waiting, Otilie finally learned of Jaroslav’s fate when he is able to call via radio telephone. He assured her that he was fine and working on making his way home as soon as he was able. It wasn’t until May 20th, 1945—on Otilie’s birthday—that their family was finally reunited after almost 5 years apart.

“On the staircase I heard familiar steps which I always knew. I ran to the door, and I had in my arms my husband after five long years of faith and hope…It was a miraculous, happy end for all of us in our family; I wished that everybody could be so happy as we were…Our family life started again with the same understanding and love. All was the same as it was five years before, but permanent scars were left in each family, in each house.”-Otilie Cebe-Habersky

With Jaroslav home from jail, there was still more work to be done to reunite the family. Mila had survived Buchenwald concentration camp and also returned home soon after Jaroslav, only to find out the truth about her children and that no one knew what had happened to them.

More about Mila’s experiences in the concentration camps is unknown. Official records mentioned that Mila was originally taken to Auschwitz after questioning the Gestapo about her husband’s death. No formal records exist listing her at Buchenwald, only her own family’s account. Toward the end of the war with the advancement of Allied forces, many of the records at the different concentration camps were completely destroyed by the fleeing Nazi army. We do know that along with the destruction of records, prisoners were forced to march from Auschwitz to Buchenwald in January of 1945 in order to avoid the advancing U.S. army. Underground resistance among the Nazi administration delayed the evacuation of prisoners from Buchenwald as U.S. forces approached the camp. On April 11, 1945 the prisoners took control of the camp and U.S. forces arrived later that afternoon (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Given that Mila was recorded as a prisoner in Auschwitz and by family accounts ended the war in Buchenwald, it seems likely that Mila would have been one of the prisoners forced on the death march from Auschwitz to Buchenwald in January of 1945 before the arrival and liberation at the hand of U.S. troops in April of the same year.

With the return of Mila from Buchenwald, Jaroslav made it his personal mission to find her children and be able to reunite them with their mother. Police leaflets with photos of Jiri and Alena were distributed across Czechoslovakia and radio broadcasts were made inviting help in locating the children. Eventually a business man in North Bohemia contacted Jaroslav, mentioning that he knew of a German family in Weinheim that adopted two children of a prominent stateman that was killed by the Nazis. Jaroslav immediately traveled to Amberg and then to Weinheim with the help of friends in the U.S. military to follow the lead, where he found his niece and nephew under the care of Dr. Georg Weiss and Elsbeth Weiss.

“I thought that they were typical Nazis, stealing and adopting children because the kids looked nice and well behaved. Soon I discovered that the Weiss couple in fact saved the children and were outstanding parents to them, giving the kids the best Christian spirit of their foster parents’ generous hearts. The Weisses remained close to the children forever, and are our good friends since that time. The reunion of the children with their mother, my sister Mila, was the best happy end I have ever fabricated and attended.”- Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky

1946

With the end of the war, Jaroslav returned to his office work as a lawyer. Eventually he was offered a job with the United Nations, specifically working with the War Crimes Commission in the United States for two years. After some discussion, Jaroslav accepted the job and liquidated his office, turning it over to friends and associates. In August of 1946, Jarsolav left Czechoslovakia, first traveling to London and then to New York where he began work with the United Nations and setting things up for the arrival of Otilie and the children. In December, after tearful goodbyes to friends and family, the rest of the family traveled to the United States, which they planned to make their home for the next two years before returning to Czechoslovakia.

After arriving in the United States, the family settled down in their first home at 14 The Waterway, Plandome Heights in New York and shipped some items from home in Czechoslovakia. Some of these items included a bedroom set, dining room furniture, china cabinet, the statue of St. Claus that Otilie placed in the window as a signal to Jaroslav many years before, and a child’s kroj, now on display at the Czech Center Museum Houston. The children quickly adapted to life in America, with Dagmar and Jack attending Manhasset High School and Ajka primary school in Manhasset. In 1947, Otilie’s mother visited them in New York for Christmas, returning to Prague in February 1948, just a few months before Jaroslav was set to finish his 2 years with the United Nations and return home with the family to Czechoslovakia. History had other plans, and the Cebe-Habersky family never returned home.

The Cebe-Habersky kroj currently housed and on display at the Czech Center Museum Houston. The child’s kroj was donated by Dagmar Cebe-Habersky’s family. Photo by author.

1948

The communist coup was something that had been lurking in the background of politics in Czechoslovakia since the end of World War 2. The USSR was one of the only countries to fully back, support, and acknowledge President Benes exiled government in London during the war. As such, Benes was very motivated to keep ties to the Soviet Union and allowed them to help direct many things in the newly establish government and nation of Czechoslovakia. Benes and the Czechoslovak government often followed direction and “suggestions” from Stalin, and the Communist party slowly gained more power and control of the politics. Non-communist political parties eventually had several chief leaders resign in protest of the monopoly of power the communist party held, leading President Benes to sign over the government to communist demands after it became clear that the non-communist parties did not have the power or ability to resist communist demands without causing an uprising (Kaplan 1987).

“Soon after her (my mother’s) departue, the Communist coup changed the situation completely. We knew that we would not return to Prague for many years to come, if ever. The Iron Curtain fell, and we could not see my mother and my husband’s parents anymore. There was no hope for a change, and our separation was complete.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

“The Communists did not like my work in the War Crimes Commission and in the American Institute. Practically all of my collaborators in the War Crimes Commission got long-term prison sentences after the communist coup in 1948-right down to the chauffeurs of our commission cars.”- Jaroslav Cebe- Habersky

All of the Cebe-Habersky’s property, assets, real estate and savings in Czechoslovakia were ceased during the Communist coup. The only belongings they had from their homeland were the ones they had been able to ship over to the United States at the beginning of Jaroslav’s time with the United Nations. Once again, their family was left to start their lives over with nothing. Jaroslav continued his work with the United Nations after the Iron Curtain fell, working as part of the War Crimes Commission, the establishment of Israel, and as part of the U.N advisory council in Somalia and Somaliland among other projects.

During this time period, on June 25th, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 in an attempt to help aid in the resettlement of displaced Europeans in the aftermath of World War 2. Originally this act restricted the number of people able to obtain U.S. Visas, including making any who entered refugee camps after December 1945 ineligible to relocate and obtain U.S. citizenship (Truman Library Institute 2019).

1950

The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 is revised, officially removing the date requirement for those seeking U.S. Visas as displaced persons in Europe (Truman Library Institute 2019).

1951

The changes in the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 most likely prompted the Cebe-Habersky family to attempt to apply for U.S. citizenship as displaced European citizens in 1951. However, a ruling from the McCarran Committee stated that U.N. staff members could not be considered displaced persons as they were protected by their privileges from the United Nations as staff. This left the entire Cebe-Habersky family in limbo, with a loss of official documentation, as their Czechoslovakian passports were no longer valid after the fall of the Iron Curtain, residing in a country where they were unable to apply to reside legally or for citizenship due to Jaroslav’s job with the U.N.

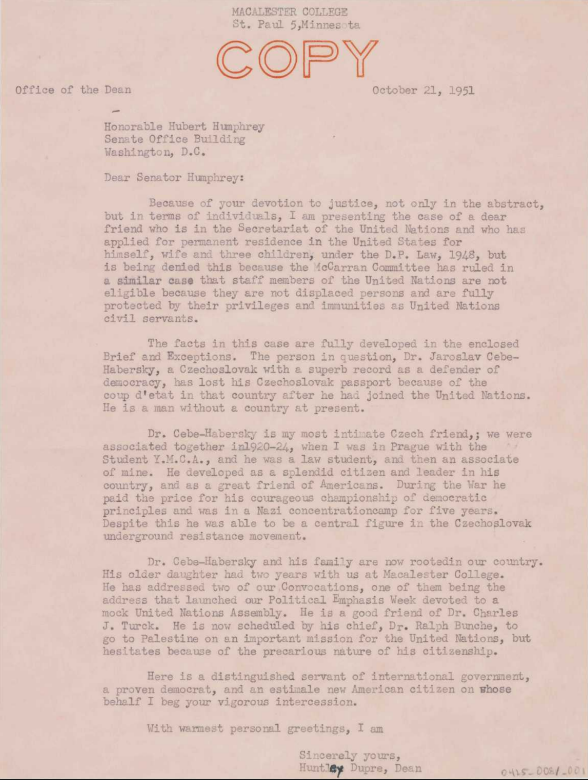

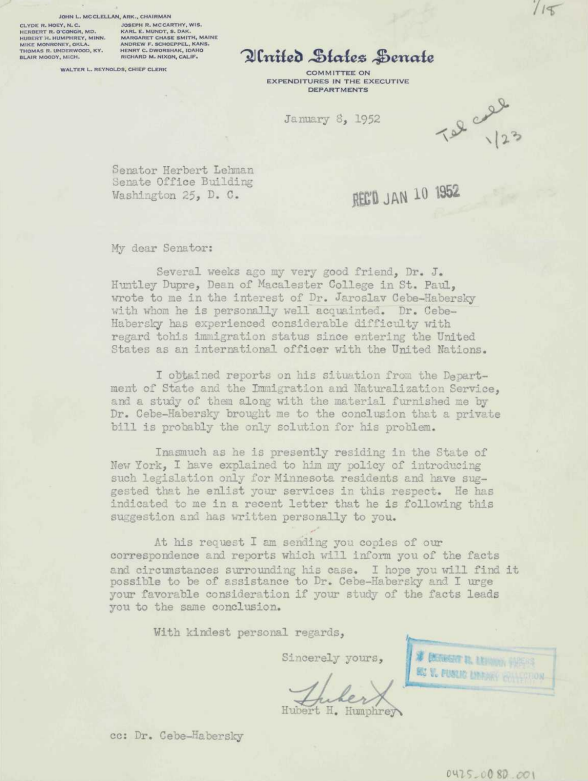

On October 21st, 1951, Dean Huntley Dupre of MaCalester College in Minnesota (where Dagmar was currently attending college) sent a letter to Senator Hubert Humphrey, arguing that the Cebe-Habersky family be given permanent resident in the United States and be allowed to apply for citizenship. At the time Jaroslav had been asked to travel to Palestine with the U.N., but was afraid to leave his family and the United States with his citizenship and legality in the balance. In response, Senator Humphrey sent a letter to Senator Herbet Lehman after meeting with Jaroslav. He suggested to Senator Lehman that a private bill to allow citizenship for the Cebe-Habersky family would be the best solution and enlisted Lehman’s help as the Cebe-Habersky family was living in New York at the time. Eventually, the Cebe-Habersky family were able to obtain U.S. citizenship, and remained in the United States, never able to return to Czechoslovakia. Jaroslav’s parents passed in 1953, and Otilie’s mother in 1960 without ever being able to see Jaroslav and Otilie’s family again.

Letter from Dean Huntley Dupre of MaCalester College (where Dagmar attended) on behalf of Dr. Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky. Taken from Columbia University Digital Collections at https://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/rbml/lehman/pdfs/0425/ldpd_leh_0425_0081.pdf.

Letter from Senator Humphrey to Senator Lehman of New York, requesting assistance for the granting of citizenship for Dr. Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky. Taken from Columbia University Digital collection at https://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/rbml/lehman/pdfs/0425/ldpd_leh_0425_0080.pdf.

Dr. Jaroslav Cebe-Habersky died in 1980 in Vermont, with Otilie Cebe-Habersky following in 1998. Their middle child Jack Vladimir Cebe-Habersky joined the United States Air Force, where he was stationed in the Netherlands and served as an assistant air liaison officer, guiding paratroopers by radio into drop zones during the Vietnam War. Captain Jack Cebe-Habersky passed away at Fort Braggs in North Carolina at age 43 in 1977. Dagma Cebe- Habersky married Rudolf M. Kroc in 1980, and pass away in 2016. It is Dagma’s daughter who donated her kroj to the Czech Center Museum Houston. As far as we know, Ajka Cebe- Habersky is still alive today.

The Cebe-Habersky child’s kroj, donated to the Czech Center Museum Houston. Photos by author.

“We were, however, grateful to live in a free country and be able to bring our children up in this hospitable country which accepted us as its citizens and gave us liberty and security.”- Otilie Cebe-Habersky

Written by Tria Van Horn

References:

Bryant, Chad. Prague in Blake: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts. 2007.

Cebe, Jarka and Otylka Cebe. “A Wartime Remembrance in Two Voices.” Edited by Alma Bennett. The South Carolina Review 46, no.1 (2013):48-77.

Cebe-Habersky, Jaroslav. Dům mrtvých: veznice Moabit a Plötzensee, 1940-1942. V Praze: Kvansnicka a Hampi, 1946.

Hajšman, Napsal Jan. Přemysl Šámal. Vydava Orbis, Praha. 1946.

Kaplan, Karel. The Short March- The Communist Takeover in Czechoslovakia 1945-1948. St Martin Press, New York. C. Hurst and Co. 1987.

MacDonald, Callum. The Killing of Reinhard Heydrick, the SS “Butcher of Prague”. New York, Da Capo Press. 1998.

Mastny, Vojtech. The Czechs under Nazi Rule- The Failure of National Resistance, 1939-1942. Columbia University Press, New York and London, 1971.

Meziřekami.cz. “The expulsion of the inhabitants of central Bohemia between 1942 and 1945 during World War II by the occupying German army and the SS.” Meziřekami.cz. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://mezirekami.cz/en-vystehovani-1/.

Miller, Roderick. “Pankrac Prison”. Frank Falla Archive. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.frankfallaarchive.org/prisons/pankrac-prison/.

Naillon, Erin. “May 1945- Prague Uprising and Liberation.” Private Prague Guide. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.private-prague-guide.com/article/may-1945-prague-uprising-and-liberation/.

Pohanka, Vojtěch. “Petschek Palace: A grand building with a dark past.” Radio Prague International. July 26, 2023. https://english.radio.cz/petschek-palace-a-grand-building-a-dark-past-8789648.

Stolpersteine. “Samalova Milada”. Stolpersteine. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://stolpersteinecz.cz/en/milada-samalova/.

Truman Library Institute. “The Displaced Persons Act of 1948”. Truman Library Institute. April 29, 2019. https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/the-displaced-persons-act-of-1948/.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Buchenwald”. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/buchenwald.

Valdová, Veronika. “Karel Janoušek.” Free Czechoslovak Air Force Association. May 8, 2012. https://fcafa.com/2012/05/08/karel-janousek/