The Czech Republic has been well known for its glass gemstone replicas, costume jewelry, and glass beads for centuries. Glass beads and costume jewelry exports from the Jizera Mountains and the city of Jablonec have helped drive the local and national economy. Given the long, historic presence of such trade in the Jablonec area, the glass jewelry industry and trade systems of what is now the Czech Republic were tremendously influenced by political events and innovations of the time globally and regionally. However, Jablonec in the Czech Republic remains, to this day, one of the most important bead centers in the world.

The first glass beads in the world began appearing within the archaeological record in Asia and North Africa starting in 1600 BCE, with glass beads in the area that now makes up the modern-day Czech Republic first arriving in the Middle to Late Bronze age as trade items from the Mediterranean. Celts in the area became the first to begin working with glass beads and jewelry during the 3rd and 1st century BCE, though they did not have the technology needed to fabricate the glass themselves, and instead worked by remelting glass into the desired form (Nový 2022: 190). However, beginning in the 13th century, the Bohemian Forest in South Bohemia became a production site for glass rosary beads due to its proximity to Nuremberg, which was a trade junction at the time. Glass making operations began to appear in the forested areas of Bohemia, as access to a steady supply of wood was important in the heating of glasshouses, the working the glass, and the creation of potash, which is an integral ingredient in making glass that creates its transparent quality (Vondruška 1989:11).

Figure 1. Examples of modern Czech beads from the Czech Center Museum Houston. Photo by author.

Throughout the 16th century, glass production in the Bohemian region often did not procuce the final products; rather, some of the workers made the glass itself, while others refined the glass into its final product. This allowed for independent production throughout all steps in the process (Vondruška 1989:12). At a time when many were forced into compulsory free field labor (corvée) and serfdom to their landlords, these independent glasshouses allowed glass masters to avoid the corvée and live in relative freedom, often only paying a small rental fee for the land they lived on (Vondruška 1989:25). Glass craft was often passed from father to son to maintain the secrecy of glass production from start to finish. As a result, glass families refused to marry anyone outside the glass craft makers. Indeed, Michael Müller, a renowned glassmaker, gave his son a packet of recipes and instructions only upon his death in order to closely guard his personal methods of creating ruby and crystal glass, among others, which set his work apart from others (Vondruška 1989:29).

The fabrication of glass costume jewelry took off in Bohemia during the 1680s when the Venetian recipe for glass goods improved enough to be able to use glass to replicate gemstones. Michael Müller and Johann Kaspar Kittel brought the original glass recipe from Italy and began experimenting with it in Southern and Northern Bohemia (Nový 2022: 191). In 1711, the city of Turnov quickly became a well-known area for the fabrication of glass stones that had the appearance of real gemstones. These glass stones were then set into cheaper materials, often emulating more expensive pieces made with authentic gemstones, and were subsequently sold at lower prices, becoming popular with those unable to purchase real stones as well as international markets. This increased interest in and demand for glass goods, exports, and trade led to the creation of the area glass guild in 1715.

The Bohemian region quickly became the most proficient at imitating a variety of gemstones and became particularly popular and famous for the unique glass paste recipe used for garnet imitation. The increase in product demand and need for skilled craftsmen also led to changes in glassworking technology, particularly with the invention of pressing pliers. These handheld pliers molded hot rods of glass into the desired bead shape, allowing glass paste to be shaped by a mold rather than needing to be worked by hand, which greatly reduced the time of labor and increased production outputs (Nový 2022: 192). In the 1720s, costume jewelry made up a third of all glass exports in the region. 1785 brought the first paste glassworks to the Jizera Mountains town of Jablonec, which would eventually become a powerhouse for glass gemstones, costume jewelry, and glass beads. The boom in Jablonec’s bead production was particularly due to the discovery of colored potash glass, which was exceptional and ideal for the creation of costume jewelry and whose colors and quality could not be replicated by the Italian and German competitors of the time (Nový 2022:193).

Figure 2. Antique pressing pliers similar to those that would have been used in the Jizera Mountains and Jablonec during this time period. Photo taken from Beadstory. https://www.beadstory.com/blog/2018/07/6-a-history-of-czech-glass-buttons.

The early 1800s saw a steady increase in glass jewelry production in the area, with 6,000 people in the Jizera mountains working in different areas of production, refining, and trading in the glass jewelry industry, with trade connections established all over the world and on every continent. Half of the exported costume jewelry in the region came from Jablonec and the Jizera Mountains. By far the largest export was cut beads, which were either sold as ready-made jewelry or as “bunt” bundles of beads.

Production efficiency further increased with new methods of creating beads. Glass rods were heated, drawn out, and then placed into molds; once pressed and cooled, the mold marks were ground down and polished (Artbeads). This unique process, as well as hand cutting with a bevel, gave the beads a shine and sparkle unique to those made in the Jablonec area. Color ranges continued to increase, as in 1844, when the secret to melting Venetian aventurine was discovered and integrated into glass production, giving Jablonec makers the ability to create glass gems and beads in colors that their competitors could not produce. The success of jewelry exports in Jablonec transformed the small village into a city that became a prominent trade center for worldwide exports (Nový 2022:195).

Figure 3. World map showing the extent of exports in glass jewelry and beads from the Jizera Mountains and Jablonec in the 1800s. Created by the author with information from Petr Nový’s “The Story of Jablonec Costume Jewelry.”

By the late 1800s, the well-established costume jewelry industry was greatly impacted by different political and historical events. Increasingly better technology allowed faster production that lowered prices, while demand for Jablonec costume jewelry allowed companies to still turn a lucrative profit. The ruling Habsburg Monarchy increased religious tolerance in 1860, which brought in many foreign entrepreneurs to the area and the costume jewelry business from different backgrounds.

This increase in entrepreneurs led to the creation of a business elite within the Jablonec glass industry. Foreign owners would reinvest profits back into the business as well as local infrastructure and in time created an industrial pyramid structure amongst the workers, with the financing traders at the top, suppliers and glass specialty workers in the middle, and a large base group at the bottom with glass workers, paste makers, and those who created semi-finished products to be refined (Nový 2022:196).

At the time, Jablonec was known for its “open air factory” setting, where numerous plants and specialty glass houses were scattered throughout the region, working on different aspects of the trade without all working under the same factory roof. The creation of the railway in 1859 further increased exports, and seed beads became increasingly popular among foreign buyers.

1873 brought the first global economic crisis, where demand for exports dropped drastically, negatively impacting the costume jewelry industry. This caused glass businesses to refine their production and practices, including the creation of metal jewelry, which helped international sales. The mid to late 1870s saw the creation of hollow blown beads through the use of multipiece molds that allowed a greater variety of beads to be made in less time.

Trade contracts expanded, particularly with Asia and Africa. British India became a popular location for the export of glass bangles that imitated traditional Chinese porcelain pieces used as decoration, talismans, or as part of different ceremonial sacrifices (Nový 2022:198). In an effort to keep up with the demand for workers and the ever-growing international exports, a specialized costume jewelry school was opened in 1880, and a business academy in 1890.

What was once considered craft production became an industry, with factory settings replacing the small independent glass shops, leading to the inclusion of machines to replace manual labor. This led to what was referred to as the “Lučany/Wiesenthal Uprising” in 1890, where starving and disgruntled workers destroyed seed bead cutting machines, leading to several clashes with the police, the deaths of three people, and multiple convictions (Nový 2022: 200).

Figure 4. Examples of exported bangles from Jablonec, currently housed in the Museum of Glass and Jewellery. Photo from the Museum of Glass and Jewellry in Jablonex nad Nisou. https://www.msb-jablonec.cz/en/expositions/the-endless-story-of-jewellery.

The early 1900s brought additional challenges to the Jablonec area and glass jewelry production. In 1905, Japanese entrepreneurs arrived as buyers, and after learning the process and mastering the technology, they returned to Japan and began producing their own beads and bangles that were then sold to India (Nový 2022:201). Although these Japanese products were often of a lower quality, their lower price was forcing Jablonec production out of the market which they had dominated for centuries. This was further complicated by the beginning of World War I. Some glass jewelry production was able to shift to wartime items such as buttons, badges, and metal studs for footwear, though the demand for glass jewelry fell sharply. After the war with the creation of Czechoslovakia, the state, wanting to create a purely Czech national jewelry production, attempted to turn the market away from Jablonec (who were mainly Bohemian-Germans) by establishing a state- run factory in Zelezny Brod, about 15 km from Jablonec (Nový 2022:202). However, this new production site did not have the long-lasting international trade relationships that Jablonec had, which in the end nevertheless left Jablonec as the main source of glass jewelry in Czechoslovakia.

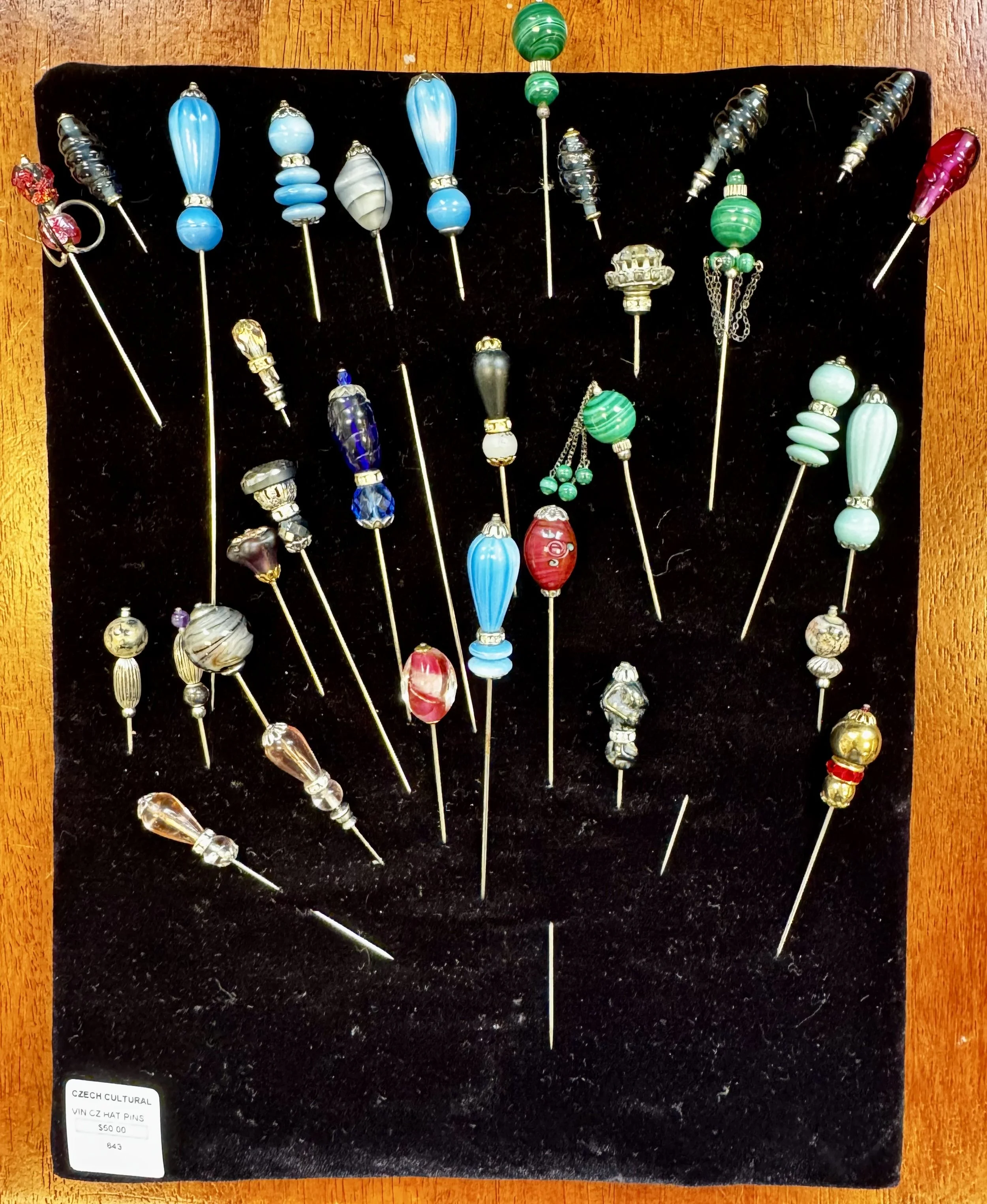

Figure 5. Vintage hat pins from the Czech Center Museum Houston. Similar ones would have been made in Jablonec. Photo by author.

The post war boom reopened international trade, particularly with the United States, India, and Egypt. In 1922, glass costume jewelry from Czechoslovakia brought in 1.5 billion Czechoslovak korunas of profit, and glass bangles (which were accounted for separately) brought in 1.8 billion korunas the same year (Nový 2022:203). Between 40,000 and 60,000 people now worked in some aspect of the glass costume jewelry industry, which made the market extremely susceptible to the effects of the Great Depression and the failing of the German Reichsmark. Although demand across international trade relationships did not significantly decrease, sale prices fell drastically, leading to an increased unemployment rate of 80% in the Jablonec area.

Figure 6. Costume Jewelry from the Museum of Glass and Jewellery in Jablonec nad Nisou. Photo taken by Martina Schneibergová, Radio Prague International. https://english.radio.cz/10-czech-museums-you-should-visit-8731249/6.

In 1938, the Jablonec area became part of Nazi Germany as a result of the Munich Agreement, where parts of Czechoslovakia were annexed to Hitler, and the Nazi government was very unsupportive of glass jewelry production and export (Nový 2022:206). This caused many of the entrepreneurs and workers to leave for Zelezny Brod, Turnov, or to flee abroad. Jewelry production was further impacted by the decision to boycott glass goods produced in this area by the United States, Canada, and Great Britain during the occupation. The start of World War II further decreased available markets for glass jewelry until Jablonec was only able to export to Germany, German allies, or neutral countries. With the end of the war and the reestablishment of Czechoslovakia in 1945, the area began to be heavily influenced by the communist Soviet Union. The Czech government nationalized the glass industry in 1948 and monopolized the production and trade of costume jewelry, greatly limiting the ability for such products to be exported internationally. In 1954, the Czechoslovak government recognized the financial potential of costume jewelry for the state (Nový 2022:207). Jablonec again became the main site for glass jewelry production. The government formed the Association of Jablonec Costume Jewelry Enterprises, which eventually came to be known as Jablonec Costume Jewelry.

Figure 7. Part of the permanent exposition at the Museum of Glass and Jewellery in Jablonec nad Nisou. Photo from the Museum of Glass and Jewellery in Jablonec nad Nisou. https://www.msb-jablonec.cz/en/expositions/the-endless-story-of-jewellery.

With the creation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the bead making industry was greatly revived in the Czech Republic, with the Jablonec area again becoming the center for Czech beads. The large scale factories have, in part, returned to their smaller, individual production roots utilizing technologies which are continually improving (Artbeads Blog). The Museum of Glass and Jewellery in Jablonec nad Nisou houses collections of beads made throughout the centuries in the area, as well as crystal glass collections. The Museum of Glass and Jewellery was instrumental in making the Czech handmade glass production and glass beads officially recognized on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage (Lazarová and Schneibergová 2021). Jablonec continues to be a center for glass jewelry, preserving this rich practice for future generations.

Written by Tria Van Horn

References:

Artbeads Blog. “The History of Czech Glass Beads”. Artbeads. Accessed August 21, 2025. https://artbeads.com/blog/history-czech-glass-beads/.

Lazarová,Daniela and Martina Schneibergová. “10 Czech museums you should visit: 6. Museum in Jablonex tells story of world-renowned Bohemian crystal glass and jewelry.” Radio Prague International. November 19, 2021. https://english.radio.cz/10-czech-museums-you-should-visit-8731249/6.

Museum of Glass and Jewellery. “History and Present”. Museum of Glass and Jewellery in Jablonec nad Nisou. Accessed August 21, 2025. https://www.msb-jablonec.cz/en/history-and-present.

Nový, Petr. “The Story of Jablonec Costume Jewelry”. Journal of Glass Studies 64, (2022): 189-212.

Vondruška, Vlastimil. “Historical Glass”. In Bohemian Glass: Tradition and…Present. Crystalex, Nový Bor, (1989).